It’s no wonder that “talk therapy”/counseling is so popular: I, and everyone I know, struggles with difficult thoughts, emotions, and circumstances. My armchair-expert opinion is that, as our society increasingly withdraws from in-person interactions and surveillance continues to spread, depression and other mental health issues will increase. We know from public data that this has already been going on for 10+ years:

- Prevalence of depression in U.S. adolescents and adults increased 60% in the past decade1

- In 2023, suicide was the #2 cause of death in people between ages 10-34 in the USA2

- From 2011 to 2021, an additional 14% of teens experienced depression, and an additional 6% seriously considered attempting suicide3

- From 2015 to 2025, depression prevalence among U.S. adults increased from 10% to 18%4

- “A 46.3% increase in likelihood of suicidal ideation among 18-to-25-year-olds was observed from 2015 to 2019 (8.3% to 12.2%)”5

The data is bleak. As a human being living in the USA, I’ve wanted to learn some effective talk therapy techniques and be a better friend to myself, my friends, and anyone in my life. I thought that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) was the best choice, as it’s widely used and performs well in scientific studies; upon researching the subject, I discovered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which is part of the “third wave of CBT”. So, technically ACT is a type of CBT, but there are some significant differences. My knowledge of CBT is limited, but here’s my summary:

- CBT is focused on the content of your thoughts: it helps you correct negative thoughts to be more realistic, while making small steps towards your goals.

- ACT is focused on your reaction to your thoughts: it helps you accept negative thoughts without letting them control you, and simultaneously take action towards your values.

So, which is better— CBT, or ACT? Based on my own research, they are both significantly effective at reducing anxiety and depression. There are several meta-analyses that attest to this67891011 as well as trials. There are some trials that pit CBT and ACT against each other (e.g. in insomnia patients), and typically the results are a close match12 but sometimes, CBT outperforms ACT13 or vice versa.14 I thought ACT outperformed CBT, but it seems the jury is still out.

Regardless, I recently read The Happiness Trap by Russ Harris (an intro to ACT, my review here), and decided to publish my notes in this format— a rough outline of what Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is, how it works, and how to apply it.

Difficult Thoughts

Most ACT theory15 is based around difficult thoughts (sometimes called “negative thoughts”). I mean, if we didn’t have them, nobody would need therapy, right? It should be obvious that any therapy is going to focus on difficult thoughts: where they come from, how to address them, how to think of them, etc. There are a few important things that ACT says about difficult/negative thoughts:

- Negative thoughts are extremely common among all people. The “default state” of our minds is to be unhappy.

- It’s very difficult to control how you think and feel. Your brain’s generation of thoughts and emotions is largely outside of your control.

- Our brain generates negative thoughts in order to help us navigate the world, but often times they’re unhelpful.

- We can and should control our response to our own thoughts and emotions.

Values

In ACT, it’s important to determine your values. Harris describes them as “how you want to treat yourself and others and the world around you.” Consider, how do you want others to describe you? Here are some examples:

- Accepting, caring, compassionate, supportive

- Assertive, fair, honest, protective

- Flexible, open, trusting, curious

- Authentic, honest, responsible, grateful

Harris recommends splitting your life into 4 categories: work, play (hobbies/rest), love (relationships), and health (physical/spiritual/mental). Then, pick some values that are important in each area, and try to improve a few at a time. It’s important to keep things realistic and achievable, so start small.

Actions and Workability

Specific actions, like “drinking alcohol” or “walking the dog” or “writing a letter” or “scrolling on Instagram”, either help you move towards your goals or away from your values. The technical term for this is workability. You should always try to perform actions that align with your values: these are called “workable” actions.

Whether or not an action is workable is up to you, and will depend on your circumstances and values. Things aren’t always black-and-white: sometimes, an action will be workable (e.g. drinking alcohol with friends) and other times, it will be unworkable (e.g. drinking alone).

Cognitive Fusion

One of the pillars of ACT is the concept of cognitive fusion, sometimes called thought fusion. The premise is that your brain is made up of two parts:

- The thinking self is like a radio that never stops playing thoughts. Usually it’s negative thoughts, but sometimes they’re happy. For example: “you should avoid that person”, “you look fat”, “you’re really good at this”, “I’m ready to go to bed”, “you’re better than everyone else”, “I don’t wanna be here right now”.

- The noticing self observes what the thinking self is producing, and reflects on it.

There are several available exercises to help mentally delineate the two parts of your self. For example, Harris recommends what is essentially meditation: spend 5 minutes doing nothing except focusing on your breathing. When a thought enters your mind (which will probably happen immediately), use your noticing self to recognize the thought, say what it is, and ignore it, focusing back on breathing. When you do this for even 5 minutes, the two parts of your self are much easier to feel and understand.

Harris likens the thinking self to a radio that we can choose to listen to, which is a helpful analogy, but I came up with another one I really like: a spinning cogwheel! (I’m excited about this one.)

When our thinking self generates a thought, our noticing self has two basic choices. First, we can pay attention to the thought, indulge it, and use it. In technical terms, this is called cognitive fusion, and it’s the default option for most people.

When we’re experiencing fusion, our noticing self is “hooked” to our thoughts/emotions, and there’s no room for reflection or controlled decision making. In this mode, your noticing self is probably either obeying the thought and indulging it (“Wow, I really am fat… I hate myself”), or you may be struggling against it (“No, I shouldn’t feel guilty for asserting myself!”). I imagine the noticing self either spinning along, or fighting the spin.

Cognitive fusion isn’t always bad! If the thought is helpful for your values, you may willingly choose fusion and indulge the thought: e.g. “Wow, you are so lovely”, “I am really enjoying this concert”, “what he did was definitely wrong; I should avoid him”.

The important part is, in ACT, we choose whether to fuse with our thoughts, or not. Instead of letting our thoughts and emotions control us, we notice each thought and make an active decision. Rather than obeying or struggling against our unhelpful thoughts, ACT encourages cognitive defusion: giving space for your thoughts to exist without letting them control you.

In ACT, the goal is to “unhook” or “defuse” from difficult thoughts. When they arise, we use our noticing self to recognize and reflect on the thought, before choosing what to do. To actually “unhook” or “defuse”, Harris recommends this 3-step strategy called ACE:

- Acknowledge your thoughts/feelings: notice it, acknowledge it, name it.

- This activates the prefrontal cortex and physically helps you respond better.

- Examples:

- “I’m noticing a thought that I’m too passive.”

- “My mind is telling me that I’m not good at this.”

- “Oh, here’s the ‘I suck’ story again.”

- Remember that your thought is just words your thinking self is generating: it may or may not be true or helpful.

- Connect with your body: make a small, controlled movement and focus on it.

- The goal is to emphasize control over your body, not to distract yourself from the thought

- Engage in what you’re doing: what can you see, hear, smell, touch, taste?

The goal of defusion is not to feel better or make the negative thoughts go away. If those things happen, great! But usually, they won’t. The goal of defusion is to prevent your thoughts and emotions from controlling you.

The Choice Point

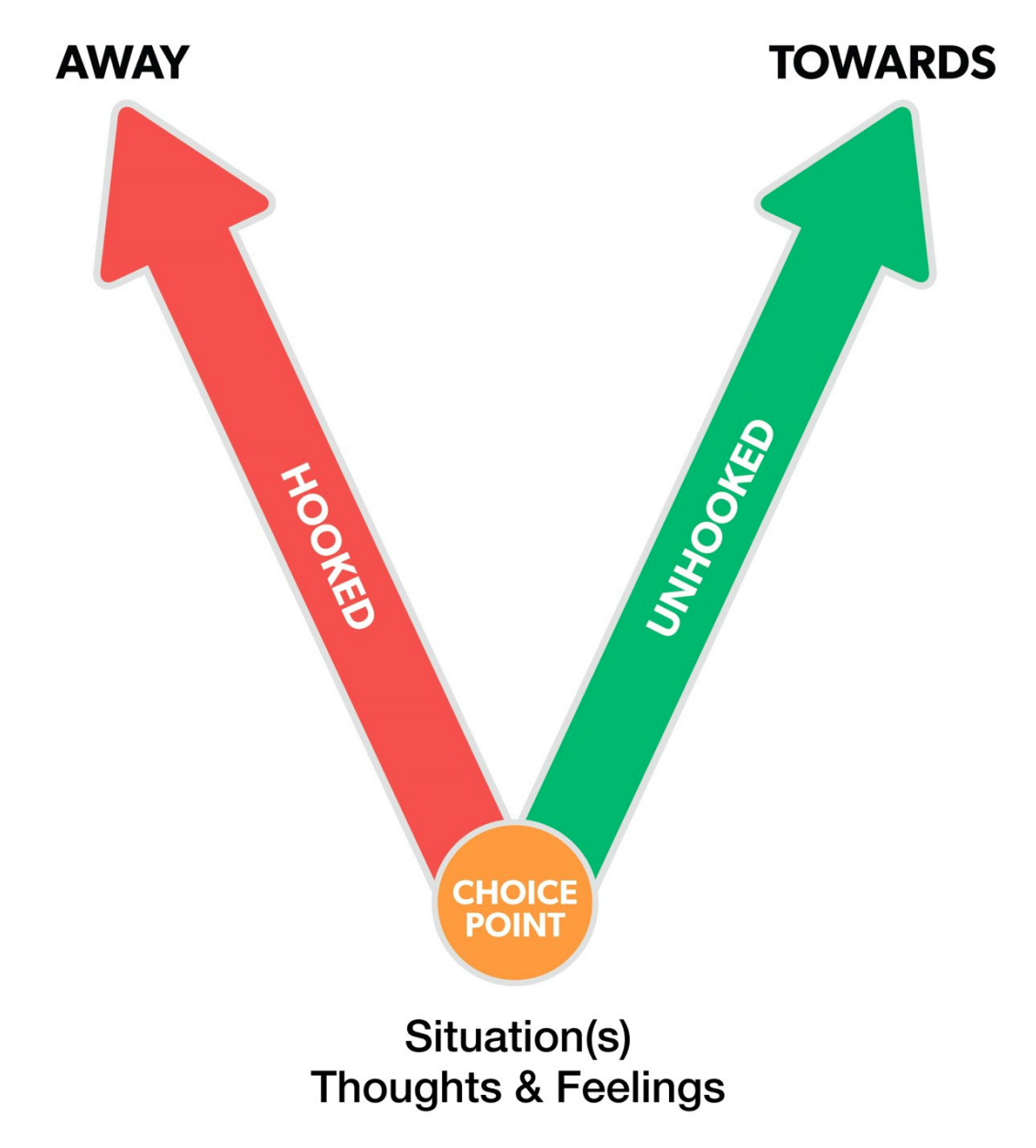

Okay, now let’s put everything together: difficult thoughts, values, workability, and cognitive fusion. This diagram is called a choice point diagram.

Source: theactmatrix.com

The diagram goes bottom-to-top:

- A difficult situation, thought, or feeling arises.

- We have a choice to either:

- Fuse with the thought (“hooked”), where we typically obey or struggle against it. This usually leads to actions that takes us away from our values.

- Defuse from the thought (“unhooked”), where we can make an informed choice about what to do next. This helps us do things that move us towards our values.

- Ideally, you should defuse, consider your values, and decide to act towards them.

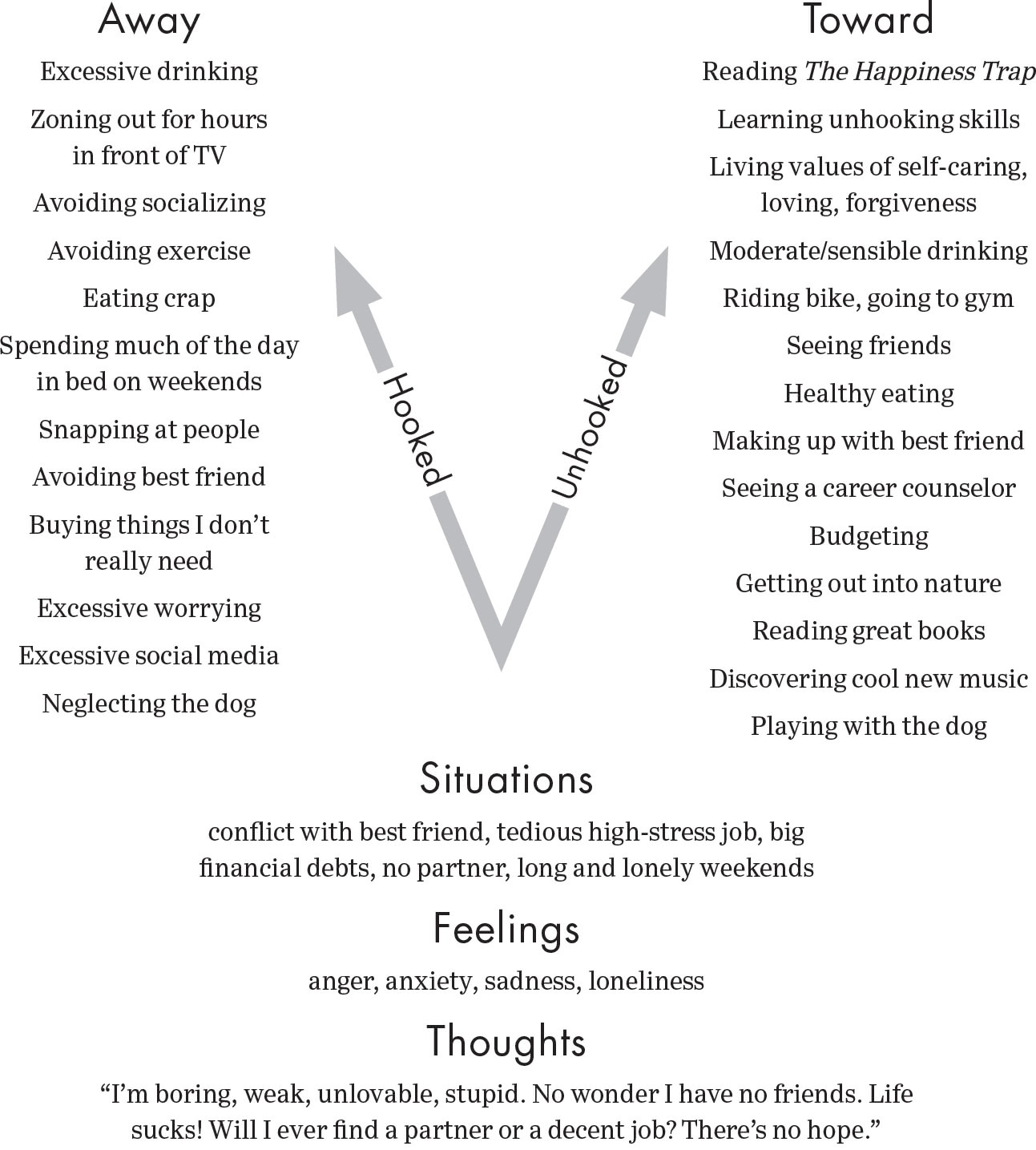

Here’s a more complete example:

Source: The Happiness Trap by Russ Harris

Finally, here are some things to remember:

- If you find yourself indulging in negative thoughts, you’ve been hooked!

- The purpose of unhooking is not to get rid of the thought/emotion/situation. It will still be there! The purpose is merely to prevent yourself from being controlled by it.

- Unhooking is an important part of ACT, but it’s only half the battle— it’s important to also move towards your values with a specific action.

Conclusion

In my view, ACT is a very practical framework for dealing with difficult situations, thoughts, and emotions. The ACT model of the “thinking self” and “noticing self” immediately made sense to me, and with very little practice, I was able to distinguish my two inner selves and start using unhooking techniques like “I’m noticing a thought of X”. It’s important to keep reasonable expectations— ACT is not a magic pill that “fixes” your negative thoughts or makes them go away, but it should help you deal with them.

I like that ACT emphasizes “committed actions”, because it grounds the theory in something actionable that you can do anytime, anywhere. And, I appreciate that ACT is a positive framework— by positive, I don’t mean “everything is sunshine and rainbows!” or “just look in the mirror and tell yourself you’re awesome!”. Rather, I mean that ACT emphasizes self-compassion: be honest with yourself about both your flaws and skills.

I’m curious how the future of CBT and ACT will evolve. I find it interesting that they have significant differences, yet are found to be similarly effective. Surely, there are improvements to be made in both models; I’ll be watching the field closely to see what comes next. In the future, I might pick up ACT Made Simple for an introduction to ACT that’s more technical and written for therapists.

Footnotes

-

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/releases/20250416.html#:~:text=New%20data,2023.%22%20This ↩

-

https://www.pew.org/en/trend/archive/fall-2023/americas-mental-health-crisis ↩

-

https://news.gallup.com/poll/694199/u.s.-depression-rate-remains-historically-high.aspx ↩

-

https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/2024/us-national-trends-and-disparities-in-suicidal-ideation-suicide-attempts-and-health-care-use ↩

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165178125003488 ↩

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2212144723000960 ↩

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032722010217 ↩

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0005789422000764?via%3Dihub ↩

-

Yes, I suffer from RAS syndrome. ↩