The Modern Biblical Mindset

Where did the Bible come from? Like most questions about the Bible, this one is not asked enough— especially by Protestants, whose sola scriptura doctrine places the Bible on a very high pedestal. Yet, many Protestants don’t know how the collection of books in the Bible came to be.

Let’s unpack that Protestant doctrine, sola scriptura (Latin for “by scripture alone”), a little more. This doctrine, among other things, emphasizes that “Scripture alone” is the main source of authority over the church.

Sola scriptura, sometimes referred to as the formal principle of the Reformation, is the belief that “only Scripture, because it is God’s inspired Word, is our inerrant, sufficient, and final authority for the church” (God’s Word Alone, 23). Notice, the basis of sola scriptura is Scripture’s inspired nature.

…While Scripture may have many human authors, it has one divine author. The Holy Spirit, Peter tells us, carried along the biblical authors so that what they said, God himself said (2 Pet. 1:21), down to the very words.

— Matthew Barrett, The Five Solas

As Barrett states, “the basis of sola scriptura is Scripture’s inspired nature.” Or, stated differently: the inspiration of Scripture is what makes it “unique among all other books”.

Inspiration means the Bible truly is the Word of God and makes the Bible unique among all other books.

— GotQuestions.org, What does it mean that the Bible is inspired?

Effectively, there is a causal relationship: if a piece of literature is divinely inspired, then it is necessarily Scripture, and is in the Bible. Thus, it follows that any book not in the Bible cannot be divinely inspired.

What is Divine Inspiration?

If I write down “God is real” on a piece of paper, is the writing on that piece of paper divinely inspired? I would argue: probably not. Merely speaking a truth about God is not enough to be considered “divinely inspired”.

There is not a strict, global definition of what it means for the Bible to be “divinely inspired”, but it can be expressed like this: the Bible is from God (in some way). Another way of expressing divine inspiration is that God had a part to play in its authorship. We can speculate the specific method(s) God uses to accomplish this, but we don’t really know.

Categorization

At this point, we’ve established that modern Protestants consider the Bible to be the set of all divinely inspired texts. If a text is from God (in some way), or if God had a part to play in its authorship, it belongs in the Bible.

Now, here’s a difficult question: does divine inspiration exist in degree? That is, can one piece of literature be “more divinely inspired” than something else?

In this question, modern and early Christians are divided. Modern Christians typically answer “no”: a text is either divinely inspired, or it’s not. These two options are exhaustive: that is, any given piece of literature will fall into one of those 2 baskets. When specifically speaking of the Biblical canon, modern Christians use the words “accepted” and “rejected” to refer to a book’s status:

- Accepted: divinely inspired; authoritative; canonical

- Rejected: not divinely inspired

Even if these are the only categories of divine inspiration, you still sometimes hear additional books taught in modern Protestant church services. Many modern pastors quote modern Christian books, or even fiction (e.g. Narnia), to make theological statements about God, or to invoke an emotional response, or simply because they like an author’s writing about God. But, these books are never seen as divinely inspired or authoritative. You’ll never hear a Christian say that C.S. Lewis “prophesied” in Mere Christianity.

Unlike us, early Christians were comfortable with varying levels of divine inspiration and canonicity. They divided literature into 4 basic categories. Here they are, with fancy Greek terms that scholars like to use:

- Homologoumena (“things agreed upon”): widely accepted across the churches; divinely inspired and highly authoritative

- Antilegomena (“spoken against”): canonicity and authority is disputed by some churches/authors

- Anagignoskomena (“the books that are read”): useful for reading/teaching; less authoritative than homologoumena, but some say they’re divinely inspired

- Rejected: not accepted

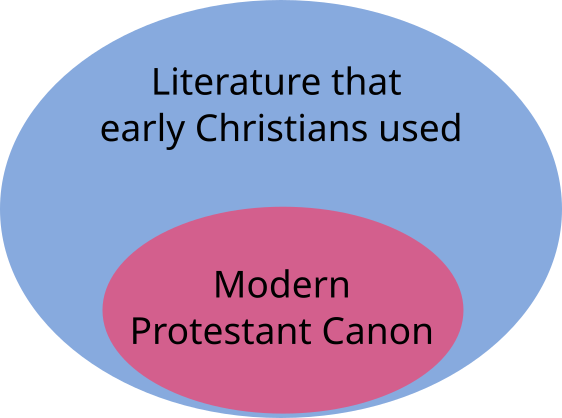

For better or worse, the earliest Christians held more nuanced views of a book’s authority and divine inspiration. Modern Protestants have a more restricted mindset for those ideas, and as a result, our canon is merely a subset of what those first Christians used.

Over time, the Christian community slowly adapted from their early nuanced views to a binary “canon-or-not” attitude. It took several hundred years before the idea of a “canon” even existed.

Anyways, you came here to learn why the canon is what it is, so let’s get on with it. We’ll look at some broad stages of Christian thoughts about canonization, and some specific early canon lists.

Earliest Christians: 0-200 CE

Early Christians had, and used, a more diverse collection of religious texts than we do today. Of course, the actual earliest Christians had 0 New Testament texts (since they weren’t written yet!). During this first period of 0-200 CE, the idea of a “closed” Old or New Testament canon simply did not exist yet.

As the books that would later become the New Testament were being written, Christians were already gathering and making important theological decisions (and arguments!). For example, Acts 15 tells the story of some early Christians gathering to decide whether Gentiles should be circumcised, or keep the law of Moses.

In early writings, we see Christians appealing to circulated letters and gospels, some of which made it into the canon (and some of which did not). It appears that early Christians were most interested in Jesus’s actual words, regardless of the source. Sometimes, we see references to Jesus’s words that don’t appear in any writing we can find. Presumably, people at this time were passing around stories about what Jesus said and did, and it’s very intuitive that these Christians would quote those materials and use them to make theological decisions.

In this period (0-200 CE), we see Christians quoting not only proto-canonical scriptures (which would later become canon), but also plenty of quotations to now-noncanonical books, even calling them “Scripture” and “divinely inspired”. For example:

- Irenaeus writes in Against Heresies (~180 CE) that the Shepherd of Hermas (and possibly also 1 Clement) is Scripture.

- Clement of Alexandria (writing ~180-200 CE) considered two noncanonical gospels to be divinely inspired (Gospel of the Egpytians, Gospel of the Hebrews), as well as 7 other noncanonical books.

- There are more examples in this chart.

A Primer on Canonization: Did God Decide?

Coming up, you’re going to see the first “canon” lists: that is, some authors start explicitly defining a set of books that are homologoumena (widely agreed upon), or antilegomena (disputed), or anagignoskomena (instructive/read aloud), or rejected entirely. The mere idea of homologoumena requires wide consensus among early churches that a specific book is Scripture. So, how were these early churches deciding that?

It’s commonly claimed that the early Christians didn’t “decide” anything— they merely “recognized” which books are divinely inspired. Here’s some examples of that claim:

It’s wrong to say that “the church” or the early church fathers determined what would be in the New Testament. They didn’t determine what would be in the New Testament—they discovered what God intended to be in the New Testament.

— Norman Geisler and Frank Turek, I Don’t Have Enough Faith To Be An Atheist

Again, it is crucial to remember that the church did not determine the canon. No early church council decided on the canon. It was God, and God alone, who determined which books belonged in the Bible.

— GotQuestions.org, How and when was the canon of the Bible put together?

The church no more gave us the New Testament canon than Sir Isaac Newton gave us the force of gravity. God gave us gravity, by his work of creation, and similarly he gave us the New Testament canon, by inspiring the individual books that make it up.

— J.I. Packer, God Speaks To Man

In my opinion, this claim is demonstrably false. We know what criteria the early Church used to determine the canon, and it’s not just “divine inspiration”.

Messy Criteria

As documented by multiple sources,1 we know that the early Church literally decided the canon! Not randomly, of course— they used these general criteria:

- Apostolicity: does the book have a link to an apostle?

- Could be directly written by apostle (e.g. Matthew’s Gospel) or more indirect (e.g. Luke’s connection to Paul)

- Some books that many early Christians used and considered authoritative (e.g. 1 Clement) were eventually excluded on this basis

- Orthodoxy: does the book “fit in” with standard orthodoxy?

- Paul appealed to orthodoxy (Galatians 1:9), which as Craig Allert points out in A High View of Scripture: “Clearly, these appeals could not have been to a closed New Testament canon since they appear in documents that later were included in the canon.”

- Inclusion of heresy (e.g. Gospel of Peter) would be a violation of this criteria.

- Catholicity and Widespread Use: was the book being used by the church at large?

- Some churches’ opinions were considered more important

To be clear, it’s not like the early Church leaders had panels of experts reviewing potential books for inclusion using a literal checklist. As with most things, it’s not that simple; this was a messy process. It took decades before the global church came to a “consensus”.2 In his landmark work The Canon of the New Testament, Bruce Metzger says:

These three criteria (orthodoxy, apostolicity, and consensus among the churches) for ascertaining which books should be regarded as authoritative for the Church came to be generally adopted during the course of the second century and were never modified thereafter. At the same time, however, we find much variation in the manner in which the criteria were applied. Certainly they were not appealed to in any mechanical fashion.

— Bruce Metzger, The Canon of the New Testament

In my opinion, trying to answer the question “Who decided the Biblical canon?” with an answer like “God” is not sufficient to explain the process. At worst, it’s dishonest (by not revealing the whole truth). At best, it’s an extrabiblical claim: whether God decided the biblical canon is an opinion you can have, but it’s not in the Bible!3

The Muratorian Fragment (~170-200 CE)

This small fragment of Latin, discovered in the early 1700s, was an incredible find. Scholars debate whether it was originally written in the late 100s or the 300s, but the consensus view is the late 100s, making it the oldest canon list we have! We only have a fragment, so it’s somewhat incomplete. For example, the discussion of the first 2 gospels is not present.

Even this early canon list maintains a large overlap with the modern New Testament canon: out of the 27 books that would eventually become the New Testament, only 5 are rejected or missing in the Muratorian Fragment, and an additional 3 books are accepted (or at least disputed) by the Muratorian Fragment.

| Book | Protestant Canon | Muratorian F. |

|---|---|---|

| Wisdom of Solomon | Rejected | Accepted |

| Apocalypse of Peter | Rejected | Disputed |

| Shepherd of Hermas | Rejected | Accepted |

| 3 John | Accepted | Not mentioned |

| 1 and 2 Peter | Accepted | Not mentioned |

| Hebrews | Accepted | Not mentioned |

| James | Accepted | Not mentioned |

Of course, this fragment says nothing about an Old Testament canon, which is an equally important piece of the puzzle.

Origen

Origen is a famous Christian teacher who spent his adult life in the early ~200s CE. He wrote many works, including Homilies on Joshua, which was translated into Latin by Rufinus of Aquileia. There is some debate about whether Rufinus translated Origen’s work accurately, but Rufinus apparently disagreed with Origen’s canon, so we have reason to believe it has been represented accurately.4 In Homilies on Joshua, he briefly discusses the writers of the New Testament and lays out a loose canon list.

Click to see the relevant text...

But when our Lord Jesus Christ comes, whose arrival that prior son of Nun designated, he sends priests, his apostles, bearing “trumpets hammered thin,” the magnificent and heavenly instruction of proclamation. Matthew first sounded the priestly trumpet in his Gospel; Mark also; Luke and John each played their own priestly trumpets. Even Peter cries out with trumpets in two of his epistles; also James and Jude. In addition, John also sounds the trumpet through his epistles, and Luke, as he describes the Acts of the Apostles. And now that last one comes, the one who said, “I think God displays us apostles last,” and in fourteen of his epistles, thundering with trumpets, he casts down the walls of Jericho and all the devices of idolatry and dogmas of philosophers, all the way to the foundations

— Origen, Homilies on Joshua, Homily 7

In this specific canon list, Origen mentions 25 of the 27 current Protestant New Testament books, exempting only Revelation and a letter of Paul (likely Hebrews, but we don’t know). Origen refers to both Revelation and Hebrews as scripture elsewhere, but also considers an additional 7 noncanonical books to be divinely inspired, such as the Gospel of Peter, 1 Clement, and the Shepherd of Hermas. He also considered many now-noncanonical Old Testament books, like Baruch and Tobit, to be divinely inspired.

When reading these early canon lists, it’s important to remember that they don’t necessarily indicate that the author had a closed canon. We see many early Christians, such as Origen, considering books outside their stated canon to be Scripture or divinely inspired.

Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History (~315 CE)

Eusebius, the bishop of Caesarea, wrote the Ecclesiastical History sometime in the early 300s. It contains a long history of Christianity, roughly from Christ to Constantine, but it also contains a canon list that splits books into 3 categories:

- Accepted: “the writings of the New Testament”

- Disputed: “the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many”

- Rejected: “the rejected writings”

Click to see the relevant passages of Ecclesiastical History...

Chapter 3:

One epistle of Peter, that called the first, is acknowledged as genuine. And this the ancient elders used freely in their own writings as an undisputed work. But we have learned that his extant second Epistle does not belong to the canon; yet, as it has appeared profitable to many, it has been used with the other Scriptures.

The so-called Acts of Peter, however, and the Gospel which bears his name, and the Preaching and the Apocalypse, as they are called, we know have not been universally accepted, because no ecclesiastical writer, ancient or modern, has made use of testimonies drawn from them.

But in the course of my history I shall be careful to show, in addition to the official succession, what ecclesiastical writers have from time to time made use of any of the disputed works, and what they have said in regard to the canonical and accepted writings, as well as in regard to those which are not of this class.

Such are the writings that bear the name of Peter, only one of which I know to be genuine and acknowledged by the ancient elders.

Paul’s fourteen epistles are well known and undisputed. It is not indeed right to overlook the fact that some have rejected the Epistle to the Hebrews, saying that it is disputed by the church of Rome, on the ground that it was not written by Paul. But what has been said concerning this epistle by those who lived before our time I shall quote in the proper place. In regard to the so-called Acts of Paul, I have not found them among the undisputed writings.

But as the same apostle, in the salutations at the end of the Epistle to the Romans, has made mention among others of Hermas, to whom the book called The Shepherd is ascribed, it should be observed that this too has been disputed by some, and on their account cannot be placed among the acknowledged books; while by others it is considered quite indispensable, especially to those who need instruction in the elements of the faith. Hence, as we know, it has been publicly read in churches, and I have found that some of the most ancient writers used it.

This will serve to show the divine writings that are undisputed as well as those that are not universally acknowledged.

— Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History

Chapter 25

Since we are dealing with this subject it is proper to sum up the writings of the New Testament which have been already mentioned. First then must be put the holy quaternion of the Gospels; following them the Acts of the Apostles.

After this must be reckoned the epistles of Paul; next in order the extant former epistle of John, and likewise the epistle of Peter, must be maintained. After them is to be placed, if it really seem proper, the Apocalypse of John, concerning which we shall give the different opinions at the proper time. These then belong among the accepted writings.

Among the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many, are extant the so-called epistle of James and that of Jude, also the second epistle of Peter, and those that are called the second and third of John, whether they belong to the evangelist or to another person of the same name.

Among the rejected writings must be reckoned also the Acts of Paul, and the so-called Shepherd, and the Apocalypse of Peter, and in addition to these the extant epistle of Barnabas, and the so-called Teachings of the Apostles; and besides, as I said, the Apocalypse of John, if it seem proper, which some, as I said, reject, but which others class with the accepted books.

And among these some have placed also the Gospel according to the Hebrews, with which those of the Hebrews that have accepted Christ are especially delighted. And all these may be reckoned among the disputed books.

But we have nevertheless felt compelled to give a catalogue of these also, distinguishing those works which according to ecclesiastical tradition are true and genuine and commonly accepted, from those others which, although not canonical but disputed, are yet at the same time known to most ecclesiastical writers — we have felt compelled to give this catalogue in order that we might be able to know both these works and those that are cited by the heretics under the name of the apostles, including, for instance, such books as the Gospels of Peter, of Thomas, of Matthias, or of any others besides them, and the Acts of Andrew and John and the other apostles, which no one belonging to the succession of ecclesiastical writers has deemed worthy of mention in his writings.

— Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History

Unfortunately, Eusebius’s list is not very specific; for example, it fails to list which of Paul’s letters are accepted.

| Book | Protestant Canon? | Eusebius |

|---|---|---|

| Hebrews | Accepted | Accepted and Disputed* |

| James | Accepted | Disputed |

| Jude | Accepted | Disputed |

| 2 Peter | Accepted | Disputed |

| 2 and 3 John | Accepted | Disputed |

| Shepherd of Hermas | Rejected | Disputed |

Athanasius’s Festal Letter 39 (367 CE)

Every year on Easter, the patriarch (highest-ranking bishop) of Alexandria, Athanasius, released a Festal Letter. In Festal Letter 39, he lays out a canon list in 3 categories:

- Accepted: “In these [books] alone is proclaimed the doctrine of godliness”

- Instructive: “there are other books besides these not indeed included in the Canon, but appointed by the Fathers to be read by those who newly join us, and who wish for instruction in the word of godliness… [they are merely] read.”

- Rejected: these “apocryphal” books “are an invention of heretics”

Click to see the relevant text...

There are, then, of the Old Testament, twenty-two books in number; for, as I have heard, it is handed down that this is the number of the letters among the Hebrews; their respective order and names being as follows. The first is Genesis, then Exodus, next Leviticus, after that Numbers, and then Deuteronomy. Following these there is Joshua, the son of Nun, then Judges, then Ruth. And again, after these four books of Kings, the first and second being reckoned as one book, and so likewise the third and fourth as one book. And again, the first and second of the Chronicles are reckoned as one book. Again Ezra, the first and second are similarly one book. After these there is the book of Psalms, then the Proverbs, next Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs. Job follows, then the Prophets, the twelve being reckoned as one book. Then Isaiah, one book, then Jeremiah with Baruch, Lamentations, and the epistle, one book; afterwards, Ezekiel and Daniel, each one book. Thus far constitutes the Old Testament.

Again it is not tedious to speak of the [books] of the New Testament. These are, the four Gospels, according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Afterwards, the Acts of the Apostles and Epistles (called Catholic), seven, viz. of James, one; of Peter, two; of John, three; after these, one of Jude. In addition, there are fourteen Epistles of Paul, written in this order. The first, to the Romans; then two to the Corinthians; after these, to the Galatians; next, to the Ephesians; then to the Philippians; then to the Colossians; after these, two to the Thessalonians, and that to the Hebrews; and again, two to Timothy; one to Titus; and lastly, that to Philemon. And besides, the Revelation of John.

These are fountains of salvation, that they who thirst may be satisfied with the living words they contain. In these alone is proclaimed the doctrine of godliness. Let no man add to these, neither let him take ought from these…

But for greater exactness I add this also, writing of necessity; that there are other books besides these not indeed included in the Canon, but appointed by the Fathers to be read by those who newly join us, and who wish for instruction in the word of godliness. The Wisdom of Solomon, and the Wisdom of Sirach, and Esther, and Judith, and Tobit, and that which is called the Teaching of the Apostles, and the Shepherd. But the former, my brethren, are included in the Canon, the latter being [merely] read; nor is there in any place a mention of apocryphal writings. But they are an invention of heretics, who write them when they choose, bestowing upon them their approbation, and assigning to them a date, that so, using them as ancient writings, they may find occasion to lead astray the simple.

— Athanasius, Festal Letter 39

Compared to the modern Protestant canon, Athanasius’s canon makes the following changes:

| Book | Protestant Canon? | Athanasius? |

|---|---|---|

| Esther | Accepted | Instructive |

| Baruch | Rejected | Accepted |

| Wisdom of Solomon | Rejected | Instructive |

| Wisdom of Sirach | Rejected | Instructive |

| Judith | Rejected | Instructive |

| Tobit | Rejected | Instructive |

| Teaching of the Apostles | Rejected | Instructive |

| Shepherd of Hermas(?) | Rejected | Instructive |

Notably, the only differences are in the Old Testament; his New Testament canon exactly matches ours. In fact, this is the first time we see this in the history of Christian literature, ~250 years after the last book was written.

Let’s not overstate the importance of Athanasius’s opinions in this letter: this list does not necessarily represent the opinions of other Christians at Athanasius’s time. For example, around the same time as this letter, Didymus the Blind, even living in the same city as Athanasius (Alexandria), probably did not consider 2 and 3 John canonical.

The Apocrypha

Beyond ~400 CE, Christianity had adopted a mostly consensus view of the New Testament canon. But, the Old Testament canon was, and remained for quite some time, less clear. It took about 1500 years from the time of Jesus, and a major church split, for firm decisions to be made. I’m speaking, of course, of the Reformation.

The Protestant Canon (Reformation/Martin Luther)

When translating the Bible into German, the famous leader of the Reformation, Martin Luther, made a decision that would have sweeping impacts on Protestant doctrine: he collected the “Apocryphal” books (e.g. Tobit, Baruch, 1 and 2 Maccabees) into a single section, stuffed them between the Old and New Testaments, and left this famous comment:

Apocrypha: These books are not held equal to the Sacred Scriptures, and yet are useful and good for reading.

— Martin Luther, Luther’s German translation of the Bible

It should be noted that even Luther occasionally treated these “apocryphal” books as divinely inspired.

Luther also eyed four of the New Testament books suspiciously. We can see this in the prefaces he wrote to each book.

In his Preface to Hebrews, which comes first in the series [of disputed books], he says, “Up to this point we have had to do with the true and certain chief books of the New Testament. The four which follow have from ancient times had a different reputation.”

— Michael Marlowe, Luther’s Treatment of the ‘Disputed Books’ of the New Testament

Here are the four books Luther regarded as suspicious:

- Hebrews

- James: “I do not regard it as the writing of an apostle”

- Jude: “it is an epistle that need not be counted among the chief books which are supposed to lay the foundations of faith.”

- Revelation: “[I] consider it to be neither apostolic nor prophetic”

Despite Luther’s negative opinions, these four New Testament books are still considered canonical today by Protestants.

Council of Trent (1545-1547)

Prompted by the Reformation, the Council of Trent responded emphatically to the issues at hand and enacted the formal Roman Catholic reply to the doctrinal challenges of the Protestants. It thus represents the official adjudication of many questions about which there had been continuing ambiguity throughout the early church and the Middle Ages. The council was highly important for its sweeping decrees on self-reform and for its dogmatic definitions that clarified virtually every doctrine contested by the Protestants.

— Encyclopedia of Britannica, Council of Trent

In response to Luther and the Reformation’s treatment of the Apocrypha (among other things), Catholic leaders organized the Council of Trent. One of the things accomplished was the setting of a closed Catholic canon.

The leaders of the Council of Trent affirmed the canon list found in the Gelasian Decree, an old Catholic document that does indeed contain a list of Christian canon. According to the Council of Trent (and old scholarship), this Gelasian Decree was written as part of the Catholic Council of Rome in 382, but we now know that is almost certainly not the case. This Gelasian Decree, from which the Council of Trent received the canon list, is probably “an anonymous work, likely from Italy, in the 6th century”.5

Prior to the Council of Trent, this canon list may have been around, but it was certainly not treated as authoritative until this point. In any case, the Catholic canon list is still the same today. It includes a lot of content not found in the Protestant canon:

| Book | Protestant Canon? | Council of Trent |

|---|---|---|

| Tobit | Rejected | Accepted |

| Judith | Rejected | Accepted |

| Wisdom of Solomon | Rejected | Accepted |

| Ecclesiasticus/Sirach/Ben Sira | Rejected | Accepted |

| 1-2 Maccabees | Rejected | Accepted |

| Baruch | Rejected | Accepted |

| Additions to Daniel and Esther | Rejected | Accepted |

Conclusion

I’ve only covered a few examples of early canon lists. There are good resources out there, like this list, that are more comprehensive. Overall, early canon lists largely overlap with the modern Protestant canon.

A few canonical books of the Bible stick out as being highly contested by multiple Christians across millennium: Hebrews, James, 2 and 3 John. Additionally, some books were clearly important to many early Christians, yet we don’t read them nowadays, like the Wisdom of Solomon or the Shepherd of Hermas.

Compared to the Protestant canon, the early Christians (first ~400 years or so) treated additional books as divinely inspired, routinely quoted from them, and considered them authoritative. Even more books were seen as “lower”, but still useful for reading and/or teaching. Books from both categories are mostly ignored by modern Protestants: perhaps this ignorance is a mistake that should be corrected.

The process of canonization was slow and messy. If you decide to stick with your denomination’s approved canon list, consider that you’re tacitly accepting that your canon list is itself divinely inspired, or that the process by which the canon list was made was itself divinely inspired/guided by God. This is the intellectual price tag of accepting a closed canon.

”Scripture” Alone?

If you’re really interested in this topic, I highly recommend A High View of Scripture? by Craig Allert. In it, he makes an important point that the doctrine of sola scriptura is fundamentally based on a Bible that the early church gave us.

There is a tacit acceptance of the institution of the historical ecclesiastical community when we accept its canon. This is why I can say that my study of the canon led me to see the indispensability of the church. This realization changes the way one thinks about theology and the Christian tradition.

— Craig D. Allert

Protestants prefer to sweep away the influence of the early church and its tradition, and just say “God gave us the canon.” This view is convenient for sola scriptura, but in my opinion, it’s also dishonest and doesn’t give credit where credit is due.

Does it makes sense to say that the fourth-century church was making very good decisions about the Bible but mostly poor ones about everything else?

…How could the leaders in this church have been correct about what went into the canon but wrong about the scriptural status of the other books?

— Craig D. Allert

Footnotes

-

For some Christians, it is simultaneously true that “God decided the canon”, and that the early church had criteria by which they, um… “selected” certain books. This seems inconsistent to me. ↩

-

There has never been a global consensus on which books belong in the Christian canon. This remains a major point of debate between Catholics and Protestants to this day. But, generally speaking, most Bibles contain a very similar set of books. ↩

-

Some disagree, pointing to John 14:25-26: “I have spoken these things while staying with you. But the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you everything, and will cause you to remember everything I said to you.” (NET) But, Jesus saying “the Holy Spirit will help you remember what I said” is not the same as something like “the eventual Protestant canon list itself is divinely inspired”. ↩

-

https://michaeljkruger.com/what-is-the-earliest-complete-list-of-the-canon-of-the-new-testament/ ↩

-

https://threepillarsblog.org/church-history/deciding-the-canon-of-scripture-damasus-and-the-council-of-rome-in-382/ ↩