Inerrancy and Inspiration

If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of biblical inerrancy, see my introduction to the topic. In essence, biblical inerrancy is somewhat self-explanatory— the Bible does not err.

The concept of biblical inerrancy is tightly coupled with a belief in the divine inspiration of the Bible, meaning that God played a role in authoring its contents. The traditional thought goes that if God authored the Bible, then it cannot contain an error.

So how, exactly, did God work with humans to write the Bible? Was every letter chosen by God, or did he allow the biblical authors to put things their own way? If they used a scribe, were both the author and scribe inspired by God, or just the scribe? Did God care about, or ensure, camera-level accuracy in every Bible story? These questions have large implications for the doctrine of biblical inerrancy, but unfortunately, these are questions the Bible does not directly address. So, Christians have spent 2000 years hypothesizing, and there is no shortage of ideas.

So, how are we to determine the “best” doctrine of inspiration, inerrancy, etc.? How can we best interpret the Scripture we are given? In the words of respected biblical scholar Michael Bird:

…a good interpretation is… something that makes sense of an author’s intention in his or her historical context… it is something that explains and accounts for all the assertions and descriptions inside a text; and it is something that is eminently relatable for us readers.

— Michael F. Bird, Seven Things I Wish Christians Knew About The Bible

The focus of this post is the second portion of his definition: a good interpretation “explains and accounts for all the assertions and descriptions inside a text”. What I am attempting to answer is this: in regards to inspiration and inerrancy, what are the “assertions and descriptions” we find inside the Bible? What “problem passages” exist that our understanding of inspiration and inerrancy must contend with?

Regardless of where you fall on the inspiration and inerrancy debate, you don’t have the privilege of chucking out passages or historical context that you don’t like. As Michael Licona puts it in his book Jesus, Contradicted, “Our understanding of Scripture should align with what we see in Scripture.” So, what do we see in Scripture?

Interpretations of 2 Timothy 3:16

2 Timothy 3:16 is one of the most commonly cited verses in support of inerrancy. It’s easy to see why— just read any modern translation:

All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.

— 2 Timothy 3:16-17, ESV

| Greek | English (NASB) |

|---|---|

| pas | All |

| graphē | Scripture |

| theopneustos | is breathed by God |

| kai | and |

| ōphelimos | profitable |

| pros | for |

| didaskalia | teaching |

| pros | for |

| elegchos | reproof |

| pros | for |

| epanorthōsis | correction |

| pros | for |

| paideia | training |

| ho | |

| en | in |

| dikaiosynē | righteousness |

from BLB

There are two incredibly important words in this verse:

- graphē: “Scripture”

- theopneustos: “is breathed by God”

These words carry extreme weight in the interpretation of this verse, and should be studied closely.

graphē

The Greek word graphē generally means writing or writings, but in the context of the New Testament, it’s usually used to refer to scripture or a specific portion of scripture (AKA the Old Testament). Some examples:

Jesus said to them, “Have you never read in the graphē: “‘The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone; this was the Lord’s doing, and it is marvelous in our eyes’?

— Matthew 21:42

At that hour Jesus said to the crowds, “Have you come out as against a robber, with swords and clubs to capture me? Day after day I sat in the temple teaching, and you did not seize me. 56 But all this has taken place that the graphē of the prophets might be fulfilled.” Then all the disciples left him and fled.

— Matthew 26:55-56

For what does the graphē say? “Abraham believed God, and it was counted to him as righteousness.”

— Romans 4:3

This word is used 50 times in the NT, and usually refers to scripture in a generic or specific sense.

Many Christians use this verse as proof of validation of the entire Bible (OT/NT), interpreting this word graphē to mean both OT and NT writings. However, this may not be the best interpretation.

The only use of graphē that explicitly refers to New Testament writings occurs in 2 Peter:

And count the patience of our Lord as salvation, just as our beloved brother Paul also wrote to you according to the wisdom given him, as he does in all his letters when he speaks in them of these matters. There are some things in them that are hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other graphē.

— 2 Peter 15-16

Clearly, the author of 2 Peter (traditionally thought to be Peter) is claiming that Paul’s writings are scripture in the same sense as OT writings. So, case closed, right? If Simon Peter considered Paul’s writings to be scripture, then it’s probably fair to say we should too, and 2 Timothy 3:16 would apply to Paul’s letters (at a minimum).

Not so fast. First, the authorship of 2 Peter is hotly debated; the scholarly consensus is that Simon Peter did not write 2 Peter— instead, it is a “pseudepigraph” or a falsely attributed text only claiming to be written by Peter. I’ve decided not to delve deeper into this topic in this section— go read about it. The point is, it’s debated.

If we assume that 2 Peter was written by a later author, it makes sense for Paul’s letters to have become canon and referenced as such. However, at the time of Paul writing 2 Timothy, no such canon had been determined. There was no agreement on what “scriptures” count as “scripture”.

In my opinion, this word is vague and we’ll probably never know exactly what Paul was referring to— this verse is probably best interpreted as referring to only Old Testament writings. Even if you choose to interpret graphē as including NT writings (as “Peter” did in 2 Peter), then you’re still left with a big question: which writings, specifically? Does graphē include the NT books not written by Paul? The Bible doesn’t answer such a question.

In conclusion, it’s near impossible to say with confidence that Paul was referring to our exact set of NT canon as it exists today when he used the word graphē in this verse, for the reasons I’ve listed above.

theopneustos

The NASB translation (and the vast majority of translations) translates theopneustos as “is breathed by God.” But what do we actually know about this word?

Unfortunately, this is a rare word— it’s possible that Paul or someone he knew invented this word. It’s only used this once in the whole New Testament. But, we can see that theopneustos appears to be a compound word based on “theos” meaning “God”, and “peustos”, meaning “to breathe” or “breathed”. For this reason, most modern translations say something like “God-breathed”.

But, scholars like John C. Poirier argue against this translation. In his book, The Invention of the Inspired Text, Poirier looks at other ancient documents to attempt to discern what the author of 2 Peter was trying to say, and concludes that it’s likely better translated as “life-giving”.

In either case, there are also grammar problems to contend with. Let’s look at the verse again, sticking with the traditional “God-breathed” translation:

…pas (all) graphē (scripture) theopneustos (God-breathed)… kai (and) ōphelimos (profitable)

So instead of “All scripture is God-breathed”, a more literal translation would be “All scripture God-breathed and…” A little less clear now, right? Entire books have been written about the use of this word theopneustos here. Is it passive, meaning “all scripture is God-breathed”? Or active, meaning “all scripture is life-giving”?

Here’s another question: is this adjective predicative, meaning the purpose of the phrase pas graphē theopneustos is to say all scripture is God-breathed, or is this adjective attributive, more like a passing thought, like “all God-breathed scripture is…”? Scholars disagree, which is unfortunate for such a critical verse.

Scholar Daniel Wallace published a lengthy argument for the former, saying that pas graphē theopneustos is an “equative clause”: “i.e., a clause in which the central point (syntactically at least) is an assertion about the subject”. He looked at similar Greek phrases inside and outside of the Bible to make this determination. But other scholars disagree— Frank W. Nelte wrote about the problems with this assumption, instead claiming that even the word kai (and) was a later addition and not present in the early Greek manuscripts, since it makes this verse very grammatically awkward, and it’s unlikely that Paul would write that.

There is a lot of debate about this word and phrase. Given the generic nature of the word graphē as I described above, I believe Paul was using this word attributively, to narrow down which graphē he was referring to— in other words, the verse would be best translated as something like this:

All writing, inspired of God, is useful for doctrine, for correction, for self-improvement, for instruction in righteousness.

Ultimately, it’s up for interpretation; the original Greek (assuming it hasn’t been modified, as some scholars have suggested) is just not specific enough.

The Bible Doesn’t Claim to be Totally Inerrant

Some portions of the Bible are considered “words of God” according to some significant biblical characters (e.g., the prophets, the law, Jesus’s words, etc.).

The Bible clearly does claim to contain God’s word, and God’s word cannot, by definition, be errant. However, the Bible does not make a generic claim that itself, as a whole is entirely God’s word. We also never see any list of “correct canon”— the NT does not point out which books are God’s word. That distinction is left to us to determine in the decades after Jesus’s death.

And ye shall consider these books, and only these books, to be God’s holy word, inspired by God and written by humans: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus…

— 2 Opinions, 3:1

If only…

The Bible Contains Contradictions

There’s really no other way to say it: the Bible contains contradictions. Of course, many Christians disagree— inerrantists hold that any apparent contradictions can be explained (or “harmonized”, see definition below) when fully investigated (these investigations often use extra-biblical historical or contextual information).

You can find plenty of lists of contradictions online, like this list of 101, or this list of 559. Again, many Christians have explanations/harmonizations for every single contradiction— strict Christian apologists would imply that there is no “unanswered contradiction”, but some of the most difficult contradictions require lengthy explanations that leave doubters unsatisfied. For a list of defenses, see Gleason L. Archer’s Encyclopedia of Bible Difficulties, which you can buy here or read online for free.

Harmonization is the process of combining different accounts of the same event into a single story.

Many harmonizations are simple and convincing, but others are not. If you read the Bible expecting to find contradictions, you’ll find them; if you believe a contradiction is impossible, you will find a way to reason your way out of it.

I’m going to identify a few problematic contradictions here, but just remember that “there is nothing new under the sun”— each of these examples has been debated to an extreme degree by scholars for decades. There are significant scholars on both sides. I challenge you to read these contradictions, read about their possible harmonizations, and consider for yourself: does the Bible contradict itself?

What is the Order of Creation?

Click to expand...

Go read the creation story in Genesis 1. I’m not attaching all the scripture here, just this (non-exhaustive) table:

| Day | What was created |

|---|---|

| 1 | Light |

| 2 | ”The expanse”, Heaven |

| 3 | Dry land, Earth, Seas, plants, vegetation, fruit |

| 4 | Sun, moon |

| 5 | Fish, birds |

| 6 | Livestock, creeping things, beasts, man (male and female) |

| 7 | God rests |

Ok, now read Genesis 2:4-9:

These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created, in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens.

When no bush of the field was yet in the land and no small plant of the field had yet sprung up—for the LORD God had not caused it to rain on the land, and there was no man to work the ground, and a mist was going up from the land and was watering the whole face of the ground— then the LORD God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature. And the LORD God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and there he put the man whom he had formed. And out of the ground the LORD God made to spring up every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food. The tree of life was in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

— Genesis 2:4-9, ESV

In Genesis 2, we have a different creation setting:

- Immediately, we see “in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens.” This suggests everything happened in one day.

- The name for God, Yahweh, is used here (it says “LORD” in the translation). This is the first time we see this name in Genesis.

- There is no “bush” or “small plant of the field” or “man” yet. Then, Yahweh makes man (not male and female simultaneously, as in Genesis 1), then plants a garden, in that order.

How is it possible for God to create both man and plants “in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens”, and also in the opposite order as Genesis 1?

Can the Disciples Take Their Staff?

Click to expand...

And he called the twelve and began to send them out two by two, and gave them authority over the unclean spirits. He charged them to take nothing for their journey except a staff—no bread, no bag, no money in their belts— but to wear sandals and not put on two tunics.

— Mark 6:7-9

Acquire no gold or silver or copper for your belts, no bag for your journey, or two tunics or sandals or a staff, for the laborer deserves his food.

— Matthew 10:9-10

And he said to them, “Take nothing for your journey, no staff, nor bag, nor bread, nor money; and do not have two tunics.

— Luke 9:3

Did Jesus tell the disciples to bring a staff, or not? You can find a possible harmonization here.

Jesus’ Genealogy

Click to expand...

Matthew 1 and Luke 3 contain genealogies of Jesus, tracing His lineage back to and Abraham and Adam, respectively. They’re too long to list here, but here’s an important snippet from each:

and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called Christ.

— Matthew 1:16

Jesus, when he began his ministry, was about thirty years of age, being the son (as was supposed) of Joseph, the son of Heli,

— Luke 3:23

Is Jesus’ grandfather Jacob or Heli? You can find a possible harmonization here.

Peter’s Denials of Jesus

Click to expand...

How many times does Peter deny Jesus? How many times does the rooster crow, and when? I’ve included the passages below if you want to read them, but here’s the problem: in Matthew, Luke, and John, the sequence is quite clearly:

- Jesus tells Peter something like “before the rooster crows, you will deny me three times.”

- Peter denies Jesus 3 times in a row.

- The rooster crows the 1st time.

Pretty straightforward. However, in Mark, we have:

- Jesus tells Peter “before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.”

- Peter denies Jesus the 1st time.

- The rooster crows the 1st time.

- Peter denies Jesus a 2nd time.

- Peter denies Jesus a 3rd time.

- The rooster crows the 2nd time.

If Peter denied Jesus exactly 3 times, these stories are impossible to reconcile— how is it possible that Peter denied Jesus just once before the first rooster crow in John, yet Peter denied Jesus three times before the first rooster crow in the other Gospels?

Possible harmonizations include:

- Mark is describing a completely separate story that is similar to the one in Matthew, Luke, and John, but happened at a different time— in other words, Peter denies Jesus 3 times on a certain day, then 3 times on a different day.

- Peter actually denied Jesus 6 times: by lining up the gospel accounts of this story, you can say that Peter denied Jesus 6 times. 3 times before the first crow, and 3 times between the first and second crow. Full explanation here.

- Another possible harmonization here.

Matthew

Jesus said to him, “Truly, I tell you, this very night, before the rooster crows, you will deny me three times.”

— Matthew 26:34

Now Peter was sitting outside in the courtyard. And a servant girl came up to him and said, “You also were with Jesus the Galilean.” But he denied it before them all, saying, “I do not know what you mean.” And when he went out to the entrance, another servant girl saw him, and she said to the bystanders, “This man was with Jesus of Nazareth.” And again he denied it with an oath: “I do not know the man.” After a little while the bystanders came up and said to Peter, “Certainly you too are one of them, for your accent betrays you.” Then he began to invoke a curse on himself and to swear, “I do not know the man.” And immediately the rooster crowed. And Peter remembered the saying of Jesus, “Before the rooster crows, you will deny me three times.”

— Matthew 26:69-75

- Jesus tells Peter “before the rooster crows, you will deny me three times.”

- Peter denies Jesus the 1st time.

- Peter denies Jesus the 2nd time.

- Peter denies Jesus the 3rd time.

- The rooster crows the 1st time.

Mark

Peter said to him, “Even though they all fall away, I will not.” And Jesus said to him, “Truly, I tell you, this very night, before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.”

— Mark 14:29-30

And as Peter was below in the courtyard, one of the servant girls of the high priest came, and seeing Peter warming himself, she looked at him and said, “You also were with the Nazarene, Jesus.” But he denied it, saying, “I neither know nor understand what you mean.” And he went out into the gateway and the rooster crowed. And the servant girl saw him and began again to say to the bystanders, “This man is one of them.” But again he denied it. And after a little while the bystanders again said to Peter, “Certainly you are one of them, for you are a Galilean.” But he began to invoke a curse on himself and to swear, “I do not know this man of whom you speak.” And immediately the rooster crowed a second time. And Peter remembered how Jesus had said to him, “Before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.” And he broke down and wept.

— Mark 14:66-72

- Jesus tells Peter “before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.”

- Peter denies Jesus the 1st time.

- The rooster crows the 1st time.

- Peter denies Jesus a 2nd time.

- Peter denies Jesus a 3rd time.

- The rooster crows the 2nd time.

Luke

Jesus said, “I tell you, Peter, the rooster will not crow this day, until you deny three times that you know me.”

— Luke 22:34

And when they had kindled a fire in the middle of the courtyard and sat down together, Peter sat down among them. Then a servant girl, seeing him as he sat in the light and looking closely at him, said, “This man also was with him.” But he denied it, saying, “Woman, I do not know him.” And a little later someone else saw him and said, “You also are one of them.” But Peter said, “Man, I am not.” And after an interval of about an hour still another insisted, saying, “Certainly this man also was with him, for he too is a Galilean.” But Peter said, “Man, I do not know what you are talking about.” And immediately, while he was still speaking, the rooster crowed.

Luke 22:55-60

- Jesus tells Peter “the rooster will not crow this day, until you deny three times that you know me.”

- Peter denies Jesus the 1st time.

- Peter denies Jesus the 2nd time.

- Peter denies Jesus the 3rd time.

- The rooster crows the 1st time.

John

Jesus answered, “Will you lay down your life for me? Truly, truly, I say to you, the rooster will not crow till you have denied me three times.

— John 13:38

The servant girl at the door said to Peter, “You also are not one of this man’s disciples, are you?” He said, “I am not.”

— John 18:17

Now Simon Peter was standing and warming himself. So they said to him, “You also are not one of his disciples, are you?” He denied it and said, “I am not.” One of the servants of the high priest, a relative of the man whose ear Peter had cut off, asked, “Did I not see you in the garden with him?” Peter again denied it, and at once a rooster crowed.

— John 18:25-27

- Jesus tells Peter “the rooster will not crow till you have denied me three times.”

- Peter denies Jesus the 1st time.

- Peter denies Jesus the 2nd time.

- Peter denies Jesus the 3rd time.

- The rooster crows the 1st time.

Abiathar or Abimelech?

Click to expand...

Then David came to Nob, to Ahimelech the priest. And Ahimelech came to meet David, trembling, and said to him, “Why are you alone, and no one with you?” And David said to Ahimelech the priest, “The king has charged me with a matter and said to me, ‘Let no one know anything of the matter about which I send you, and with which I have charged you.’ I have made an appointment with the young men for such and such a place. Now then, what do you have on hand? Give me five loaves of bread, or whatever is here.” And the priest answered David, “I have no common bread on hand, but there is holy bread—if the young men have kept themselves from women.” And David answered the priest, “Truly women have been kept from us as always when I go on an expedition. The vessels of the young men are holy even when it is an ordinary journey. How much more today will their vessels be holy?” So the priest gave him the holy bread, for there was no bread there but the bread of the Presence, which is removed from before the LORD, to be replaced by hot bread on the day it is taken away.

1 Samuel 21:1-6

One Sabbath he was going through the grainfields, and as they made their way, his disciples began to pluck heads of grain. And the Pharisees were saying to him, “Look, why are they doing what is not lawful on the Sabbath?” And he said to them, “Have you never read what David did, when he was in need and was hungry, he and those who were with him: how he entered the house of God, in the time of Abiathar the high priest, and ate the bread of the Presence, which it is not lawful for any but the priests to eat, and also gave it to those who were with him?” And he said to them, “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath. So the Son of Man is lord even of the Sabbath.”

— Mark 2:23-28

In 1 Samuel, we see the story of David traveling to see Ahimelech the priest, who gives David and his men the holy bread to eat. In Mark, Jesus references this story to justify Jesus and his disciples plucking grain even on the Sabbath. But Jesus says “in the time of Abiathar the high priest”, when 1 Samuel calls Ahimelech the priest. Who was the priest?

David B. Wallace presents 5 possible solutions in this article, Mark 2:26 and the Problem of Abiathar:

- Text-Critical: The text as it stands is incorrect and needs to be emended.

- Dominical: Jesus himself made a mistake or was intentionally midrashic (i.e., he embellished the OT story to make his point).

- Source-critical: Mark’s source (Peter?) made a mistake in reporting Jesus’ words, or else was intentionally midrashic.

- Mark erred in reporting what his source said, or was intentionally midrashic.

- Hermeneutical: The interpretation that “when Abiathar was high priest” is incorrect.

Editorial Fatigue

A concept related to biblical contradictions is editorial fatigue. This approach, began by biblical scholar Mark Goodacre in the late 90’s, attempts to understand differences between the gospels by looking at the way they relate to one another. Goodacre describes editorial fatigue like “continuity errors”:

Editorial fatigue is a phenomenon that will inevitably occur when a writer is heavily dependent on another’s work. In telling the same story as his predecessor, a writer makes changes in the early stages which he is unable to sustain throughout. Like continuity errors in film and television, examples of fatigue will be unconscious mistakes, small errors of detail which naturally arise in the course of constructing a narrative. They are interesting because they can betray an author’s hand, most particularly in revealing to us the identity of his sources.

— Mark Goodacre, Fatigue in the Synoptics

The Marcan Priority Theory, the idea that the Gospel of Mark was written first among the four gospels, is generally accepted by most biblical scholars. Goodacre is one proponent of Marcan priority, and shows evidence of editorial fatigue in both Matthew and Luke, who used Mark as a source when composing their gospels.

Click here to see an example...

I’m going to be lazy here and just quote Goodacre’s example, because I can’t write it better myself: let’s look at “the Death of John the Baptist (Mark 6.14-29 // Matt 14.1-12)”. First, the scripture:

King Herod heard of it, for Jesus’ name had become known. Some said, “John the Baptist has been raised from the dead. That is why these miraculous powers are at work in him.” But others said, “He is Elijah.” And others said, “He is a prophet, like one of the prophets of old.” But when Herod heard of it, he said, “John, whom I beheaded, has been raised.” For it was Herod who had sent and seized John and bound him in prison for the sake of Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife, because he had married her. For John had been saying to Herod, “It is not lawful for you to have your brother’s wife.” And Herodias had a grudge against him and wanted to put him to death. But she could not, for Herod feared John, knowing that he was a righteous and holy man, and he kept him safe. When he heard him, he was greatly perplexed, and yet he heard him gladly. But an opportunity came when Herod on his birthday gave a banquet for his nobles and military commanders and the leading men of Galilee. For when Herodias’s daughter came in and danced, she pleased Herod and his guests. And the king said to the girl, “Ask me for whatever you wish, and I will give it to you.” And he vowed to her, “Whatever you ask me, I will give you, up to half of my kingdom.” And she went out and said to her mother, “For what should I ask?” And she said, “The head of John the Baptist.” And she came in immediately with haste to the king and asked, saying, “I want you to give me at once the head of John the Baptist on a platter.” And the king was exceedingly sorry, but because of his oaths and his guests he did not want to break his word to her. And immediately the king sent an executioner with orders to bring John’s head. He went and beheaded him in the prison and brought his head on a platter and gave it to the girl, and the girl gave it to her mother. When his disciples heard of it, they came and took his body and laid it in a tomb.

— Mark 6:14-19

At that time Herod the tetrarch heard about the fame of Jesus, and he said to his servants, “This is John the Baptist. He has been raised from the dead; that is why these miraculous powers are at work in him.” For Herod had seized John and bound him and put him in prison for the sake of Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife, because John had been saying to him, “It is not lawful for you to have her.” And though he wanted to put him to death, he feared the people, because they held him to be a prophet. But when Herod’s birthday came, the daughter of Herodias danced before the company and pleased Herod, so that he promised with an oath to give her whatever she might ask. Prompted by her mother, she said, “Give me the head of John the Baptist here on a platter.” And the king was sorry, but because of his oaths and his guests he commanded it to be given. He sent and had John beheaded in the prison, and his head was brought on a platter and given to the girl, and she brought it to her mother. And his disciples came and took the body and buried it, and they went and told Jesus.

— Matthew 14:1-12

Now, Goodacre’s explanation of the evidence for editorial fatigue:

For Mark, Herod is always ‘king’, four times in the passage (vv. 22, 25, 26 and 27). Matthew apparently corrects this to ‘tetrarch’. This is a good move: Herod Antipas was not a king but a petty dependent prince and he is called ‘tetrarch’ by Josephus (Ant. 17. 188; 18. 102, 109, 122) (6). More is the shame, then, that Matthew lapses into calling Herod ‘the king’ halfway through the story (Matt 14.9), in agreement with Mark (6.26).

Styler points further to a more serious inconsistency in the same verse. The story in Mark is that Herodias wanted to kill John because she had a grudge against him,

‘But she could not because Herod feared John, knowing that he was a righteous and holy man, and he protected him. When he heard him, he was greatly perplexed; and yet he liked to listen to him.’ (Mark 6.19f).

In Matthew’s version of the story, this element has dropped out: now it is Herod and not Herodias who wants him killed (Matt [47] 14.5). When Mark, then, speaks of Herod’s ‘grief’ (perilupoV) at the request for John’s head, it is coherent and understandable: Herodias demanded something that Herod did not want. But when Matthew in parallel speaks of the king’s grief (kai luphqeiV o basileuV, Matt 14.9), it makes no sense at all. Matthew had told us, after all, that ‘Herod wanted to put him to death’ (14.5).

The obvious explanation for the inconsistencies of Matthew’s account is that he is working from a source. He has made changes in the early stages which he fails to sustain throughout, thus betraying his knowledge of Mark. (7) This is particularly plausible when one notes that Matthew’s account is considerably shorter than Mark’s: Matthew has overlooked important details in the act of abbreviating. (8) It would be difficult, one would imagine, to forge a convincing argument against this from the perspective of Matthean priority. (9)

Strange Use of the Old Testament

Then when Judas, his betrayer, saw that Jesus was condemned, he changed his mind and brought back the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and the elders, saying, “I have sinned by betraying innocent blood.” They said, “What is that to us? See to it yourself.” And throwing down the pieces of silver into the temple, he departed, and he went and hanged himself. But the chief priests, taking the pieces of silver, said, “It is not lawful to put them into the treasury, since it is blood money.” So they took counsel and bought with them the potter’s field as a burial place for strangers. Therefore that field has been called the Field of Blood to this day. Then was fulfilled what had been spoken by the prophet Jeremiah, saying, “And they took the thirty pieces of silver, the price of him on whom a price had been set by some of the sons of Israel, and they gave them for the potter’s field, as the Lord directed me.”

— Matthew 27:3-10

It appears that Matthew is quoting Jeremiah in this passage. However, you won’t find his quote anywhere in Jeremiah, or anywhere in the Old Testament.

The most direct quotation is found in Zechariah 11:

Then I said to them, “If it seems good to you, give me my wages; but if not, keep them.” And they weighed out as my wages thirty pieces of silver. Then the LORD said to me, “Throw it to the potter”—the lordly price at which I was priced by them. So I took the thirty pieces of silver and threw them into the house of the LORD, to the potter.

— Zechariah 11:12-13

There are similarities between this passage and Matthew (e.g., 30 pieces of silver, a potter, thrown money), but also differences (e.g., no mention of a field). Most likely, Matthew is referring to this passage in addition to scattered parts of Jeremiah, such as Jeremiah 18:2-6 (God is like a potter) and this passage from Jeremiah 32:

Jeremiah said, “The word of the LORD came to me: Behold, Hanamel the son of Shallum your uncle will come to you and say, ‘Buy my field that is at Anathoth, for the right of redemption by purchase is yours.’ Then Hanamel my cousin came to me in the court of the guard, in accordance with the word of the LORD, and said to me, ‘Buy my field that is at Anathoth in the land of Benjamin, for the right of possession and redemption is yours; buy it for yourself.’ Then I knew that this was the word of the LORD. “And I bought the field at Anathoth from Hanamel my cousin, and weighed out the money to him, seventeen shekels of silver.

— Jeremiah 32:6-9

According to many scholars, Matthew is doing some sort of combination and re-interpretation of Old Testament passages and prophecies. Yet, he attributes the words as being spoken by Jeremiah.

Matthew appears to be drawing his citation from both Zechariah and Jeremiah and blending them together to make the point he wants to make.

— Bill Mounce, Bible Contradiction: Matthew’s Citation of Jeremiah (Matt 27:9)

Jesus’s Words are Quoted Differently

The gospels claim to contain Jesus’s words, yet they’re given differently in each gospel. Take, for example, the parable of the mustard seed:

He put another parable before them, saying, “The kingdom of heaven is like a grain of mustard seed that a man took and sowed in his field. It is the smallest of all seeds, but when it has grown it is larger than all the garden plants and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches.

— Matthew 13:31-32

And he said, “With what can we compare the kingdom of God, or what parable shall we use for it? It is like a grain of mustard seed, which, when sown on the ground, is the smallest of all the seeds on earth, yet when it is sown it grows up and becomes larger than all the garden plants and puts out large branches, so that the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.”

— Mark 4:30-32

He said therefore, “What is the kingdom of God like? And to what shall I compare it? It is like a grain of mustard seed that a man took and sowed in his garden, and it grew and became a tree, and the birds of the air made nests in its branches.”

— Luke 13:18-19

Each of these gospels is claiming to quote Jesus’s words, yet they’re all different. Which do you think is more likely?

- Jesus told this parable 3 different times, using slightly different wording each time. Matthew, Mark, and Luke wrote down only the one version they heard, but not the other two.

- Jesus told this parable one time, and each gospel writer either remembers it a little differently, or chooses to write it down differently to serve their gospel purposes.

Like most Christians, I lean towards #2. We’re willing to admit here that even when the Bible claims to quote the words of God, we could be getting a man’s interpretation of it (or divinely inspired interpretation, if you prefer to say that).

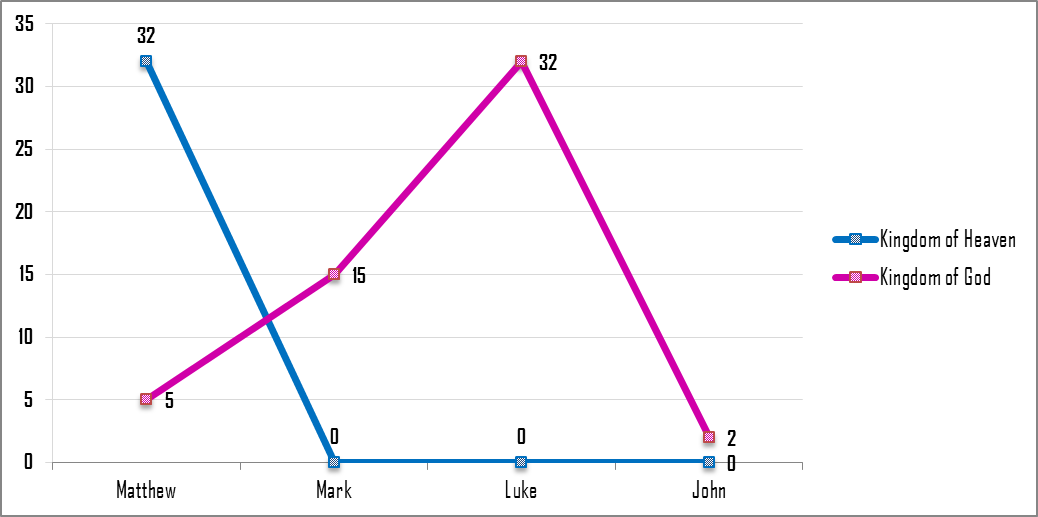

Consider the following graph, comparing Matthew’s common usage of the phrase “Kingdom of Heaven” more frequently than “Kingdom of God”:

Again, I ask: which do you think is more likely?

- Mark, Luke, and John either never heard Jesus say “kingdom of heaven” or decided to not write it down.

- Either Matthew or Mark/Luke/John misremembered or paraphrased.

Jesus Spoke in Aramaic

It’s widely accepted that Jesus knew and spoke in Aramaic, Greek, and Hebrew, but he primarily spoke in Aramaic. This would include his parables and teachings among the disciples and Jews.

However, our earliest manuscripts of the Gospels are all written in Greek. When they quote Jesus, they almost always quote him speaking in Greek. There are some exceptions; for example, in Mark, when Jesus is about to die on the cross, he speaks Aramaic that resembles the name of Elijah, leading to confusion in the crowd. Mark needed to quote Aramaic in this situation to explain the crowd’s reaction.

And at the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, “Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?” which means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” And some of the bystanders hearing it said, “Behold, he is calling Elijah.” And someone ran and filled a sponge with sour wine, put it on a reed and gave it to him to drink, saying, “Wait, let us see whether Elijah will come to take him down.”

— Mark 15:34-36

If Jesus taught in Aramaic, then we don’t have his literal words in the Gospels— the authors translated them into Greek.

After all, Jesus probably spoke in Aramaic and the New Testament is written in Greek. So, even in the original, the New Testament authors were translating what Jesus said.

— Norman Geisler, Do We Have the Exact Words of Jesus in the Gospels?

The Gospels are Greco-Roman Biographies

Dr. Mike Licona, a Christian NT scholar, argues in his two books Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? and Jesus, Contradicted (my review here, fantastic book) that the Gospels should be read in light of their literary genre. For example, we wouldn’t watch Rocketman, the 2019 Elton John biopic, as if it displays exact, fully historically accurate accounts of his life. Yes, you may learn some generic truths about Elton John, but the movie primarily exists to offer entertainment value— it embellishes details and stories to make a good movie.

In this way, when we consume literature, our understanding of its literary genre affects our interpretation of it. So when we read the Gospels, we should consider: what type of literature is this, and how did the authors intend for it to be read?

In his books, Dr. Licona makes the case that the gospels are Greco-Roman biographies. He has analyzed biographies written during Gospel times to determine what standard of error we should expect from the Gospels. I encourage you to read the book or my review, but I’ve quoted another review below to summarize Licona’s conclusions:

Licona affirms that even the best historians and biographers of Jesus’s day were not committed to the kind of precision we often expect for historiography today. Writers told stories “in a manner that entertained, provided moral guidance, emphasized points they regarded as important, and paint a portrait of important people” (p. 198). Their adaptations were “not intended to distort the truth but to communicate it more effectively” (p. 198)

…

Licona’s work is particularly helpful in placing the Gospels in their first century literary context. Most NT scholars today acknowledge that the closest first century genre to the NT Gospels is Greco-Roman biography. The Evangelists were not only Spirit-inspired writers, but also authors deeply embedded in their own time and place.

…

Licona concludes that “a truly high view of the Gospels as holy writ requires us to accept and respect them as God has given them to us rather than to force them into a frame shaped by how we think he should have” (p. 201, italics mine).

— Mark L. Strauss, thegospelcoalition.org

Paul’s Memory Lapse

In Jesus, Contradicted, Licona discusses Paul’s memory lapse in 1 Corinthians:

I thank God that I baptized none of you except Crispus and Gaius, so that no one may say that you were baptized in my name. (I did baptize also the household of Stephanas. Beyond that, I do not know whether I baptized anyone else.)

— 1 Corinthians 1:14-16

See Licona’s discussion:

Then there is Paul’s memory lapse in 1 Corinthians 1:16 pertaining to whether he had baptized anyone outside the household of Stephanus. Surely, we are not to imagine the Holy Spirit asking Paul not to get ahead of him but instead to take a break while the Holy Spirit checked heaven’s records, only to find the relevant one missing! Yet such occurrences would be required if the biblical authors wrote as the Holy Spirit was dictating to them what to write. After all, Paul may not have recalled everyone he had baptized. But the Holy Spirit knew. These observations clearly reveal a human element in Scripture; an element that includes imperfections and, thus, rules out divine dictation.

— Michael Licona, Jesus, Contradicted

I tend to agree with Licona: at a minimum, the view the God dictated every single letter of Scripture is untenable in the face of this passage.

”Closed” Biblical Canon?

I don’t wish to cover the entire history of the biblical canon here, but I’d like to touch on one specific issue: the deuterocanonical books, which Protestants call the Apocrypha. Protestants don’t include any of these books in the OT canon, but the Catholic bible does include some, including: Tobith, Judith, additions to Esther, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Baruch, Letter of Jeremiah, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and additions to Daniel. Protestants and Catholics debate the canonicity of these books to this day.

It’s disputed whether early church leaders generally accepted the canonicity of the deuterocanonical books. Protestants claim “The OT apocryphal books… were not considered canonical by the Jews of Jesus’s own time, nor by most of the early church fathers” (thegospelcoalition.org), while Catholics claim “these books had been regarded as canonical since the beginning of Church history” (catholic.com). After looking into it myself, it’s fair to say they’re both right— there were significant historical church leaders on both sides.

The deuterocanonical books were included in the Septuagint, the earliest Greek translation of the Bible. Jesus sometimes quotes the Septuagint in the gospels (e.g., Mark 7:6-7), though some Christians believe Jesus actually spoke the original Hebrew and the gospel authors translated since they were writing in Greek. This argument has been used to push for their inclusion in the OT canon.

The Council of Rome, a regional council held in 382 AD, established a canon of scripture that included most of the deuterocanonical books (see here for a translation of the Council’s findings). Though, we only know of this council from a potentially dubious source and it may not have happened. The Council of Laodicea, only ~20 years prior, was another regional council that affirmed some deuterocanonical books like Baruch (but omitted Revelation). These councils are further evidence of the disputed history of “official” OT canon.

I think Michael Kruger’s take on what happened during the 1500s is fair:

Due to the fact that the Apocrypha was the basis for many controversial doctrines (e.g., purgatory), the Reformers revisited the issue of which books were properly Scripture, concluding that the OT Apocrypha should not be the basis for Christian doctrine.

In a counter-Reformation move, the Roman Catholic church at the Council of Trent (1546) made an official declaration that the Apocrypha was henceforth to be regarded as Scripture. So, despite the controversial and mixed status of the Apocrypha throughout the history of Christianity, the Roman Catholic church made their view official, creating a division with Protestants over this issue that continues to this day.

— Michael Kruger, The Apocrypha, thegospelcoalition.org

This is a problem for biblical inerrancy because the Christian canon is an open problem. Modern Christians disagree on which books belong in the Bible. And unlike the earliest historical Christians, Protestants place basically no authority on any of the deuterocanonical books, which could contain the inspired word of God.

Conclusion

However we define inspiration and inerrancy, we must contend with what we see in the Bible. What we see are contradictions in historical narratives, paraphrasing and translation of Jesus’s words, memory lapses, and editorial fatigue, among other things

These concepts are hard. They can create doubt in the minds of some conservative Christians, who have been all-too-commonly taught to see the Bible’s truth as brittle, ready to crack over a single error. I encourage you to study these passages, and consider what a good interpretation of inspiration and inerrancy looks like.