The Reason for God is probably the best “everything Christianity” book I’ve read so far.

When I say “everything Christianity” book, I mean that Timothy Keller pretty much touches it all— what Christianity is, how you become a Christian, common arguments against Christianity and their common Christian responses, discussion on the Problem of Evil, the evidence for the resurrection, science vs. Christianity, naturalism and moral relativism, etc. He explicitly says this book is one of his “cases for belief in Christianity to those who don’t believe”, and I saw that come through clearly. Tim Keller spent years working with young, progressive New Yorkers in Manhattan who struggled with Christianity’s common moral or logical problems. He drew upon that experience to write this book.

Among Christian “apologists” (if Keller can be considered one) and their books, I found The Reason for God to be fairly humble. For me, this is really important, especially if his goal is to convince readers. He readily admits that, unlike what you might read on social media, neither atheism nor Christianity are going away anytime soon: “the time for making elegant dismissive gestures toward the other side is past.”

It is no longer sufficient to hold beliefs just because you inherited them. Only if you struggle long and hard with objections to your faith will you be able to provide grounds for your beliefs to skeptics, including yourself, that are plausible rather than ridiculous or offensive… and, just as important… such a process will lead you… to respect and understand those who doubt.

…since our respective views of reality are based in great part on faith, we must stop expecting the rest of the world to simply bow its knee to our particular set of faith instructions. We should not attack, mock, and speak as if our beliefs are self-evident to all decent people. On the other hand, since all worldviews are also based on reason, we should try to help the other side see the reasons for our faith, seeking to make our views as intelligible as possible to people who inhabit different moral frameworks.

— Timothy Keller

I couldn’t agree more. Even as Christians, we should be analyzing our faith and doubts. In a podcast, scholar Michael Licona once referred to this concept as “inoculation vs insulation”: it’s better to expose Christians to doubts than try to hide them, and in the process, we’ll all gain some respect for the other side.

Many Christians claim that their arguments for faith are so strong that all who reject them are simply closing their minds to the truth out of fear or stubbornness.

— Timothy Keller

This kind of attitude (not of Keller, but of the ones he is discussing) is so distasteful and arrogant. I recently read a book that made exactly this kind of claim (I Don’t Have Enough Faith To Be An Atheist).

But, this is definitely not not an unbiased book. Keller, of course, takes the position that Christianity is the only true religion. He makes the classic Christian comparison between salvation by works (other world religions) and salvation by faith (Christianity); also unlike other popular world religions, Jesus came as a savior, not just a teacher.

The Clues of God

Keller spends a good deal of the book discussing the “clues of God”, or arguments that he would say point towards God, but not in a definite way, e.g. the Big Bang, the Fine Tuning argument, the regularity of nature’s laws, and our innate sense of something supernatural.

Every one of [the clues] is rationally avoidable. However, their cumulative effect is, I think, provocative and potent.

— Timothy Keller

Like Pascal in the 1600s once argued, Keller asserts we all have a God-shaped hole in our hearts; we know that something is wrong with the world, and we all long for “cosmic significance”. People attempt to fill that with jobs, achievement, family, power, but it doesn’t work.

Everybody has to live for something. Whatever that something is becomes “Lord of your life,” whether you think of it that way or not. Jesus is the only Lord who, if you receive him, will fulfill you completely, and, if you fail him, will forgive you eternally.

— Timothy Keller

His other primary argument for God is “moral obligations”. Essentially, even those who tout moral relativism, there are absolute moral wrongs that make us feel an obligation to intervene (e.g. murdering newborns).

If there is no God, then there is no way to say any one action is “moral” and “immoral” but only “I like this.”

…

If the premise (“There is no God”) leads to a conclusion you know isn’t true (“Napalming babies is culturally relative”) then why not change the premise?

— Timothy Keller

Atheists like Richard Dawkins argue that evolution, or natural selection, is the “clue-killer” for all of these things. Evolution explains why we have an innate propensity to believe in the supernatural (e.g., our ancestors who imagined something around the corner survived). But Keller points out the contradiction hidden in this argument when he says “If our cognitive faculties only tell us what we need to survive, not what is true, why trust them about anything at all?”

Contradiction and Hypocrisy

In the counterargument chapters, Keller frequently used a single tactic to disarm some of the most common anti-Christian arguments: contradiction and hypocrisy. Many of these arguments, when applied to themselves, just fall apart. Things aren’t as cut-and-dry and people like to think.

In the West, many people don’t like Christianity’s exclusive claim to truth. The prevalence of the “coexist” bumper sticker is a sign that a more palatable religion would give truth to all religions. This is called religious pluralism, and it’s a common view today. But I just don’t see the merit, besides the idea being easier to swallow than Christianity being true. To claim that all religions are compatible is just false— every major world religion makes contradictory truth claims about the world, God, their prophets/spiritual leaders, and how to respond. If you insist all religions point to the same God, you’ve rejected the religions as they are, and replaced them with your own version. You’re guilty of doing the same thing you claim to reject— making an absolute, objective, exclusive truth claim.

How could you possibly know that no religion can see the whole truth unless you yourself have the superior, comprehensive knowledge of spiritual reality you just claimed that none of the religions have?

…

Skeptics believe that any exclusive claim to a superior knowledge of spiritual reality cannot be true. But this objection is itself a religious belief.

— Timothy Keller

Another common complaint is that Americans are only Christian because they grew up in America, and people born in other similarly religious countries just adapt to their local culture as well. In other words, you can’t trust your culture’s conditioning to tell you the truth about the world. But in essence, this is like saying that truth is unknowable, and a statement like that also comes from biased cultural conditioning.

You can’t say, “All claims about religion are historically conditioned except the one I am making right now.” If you insist that no one can determine which beliefs are right and wrong, we should we believe what you are saying?

— Timothy Keller

Okay, one more: another common American take is to simply “leave religion out of politics”, suggesting people leave their religion at home. Keller rightly answers that “religion” is often a vague term, and even those who deny religion hold a close set of beliefs about the world that would fit its definition (they may call it a “worldview”). There is no such thing as “neutral and objective” arguments.

…a very strong case can be made that all moral positions are at least implicitly religious.

— Timothy Keller

In this section was my favorite quote in the book, from C. John Sommerville, who aptly described what it’s like to “evaluate a religion”:

You can’t evaluate a religion except on the basis of some ethical criteria that in the end amounts to your own religious stance.

— C. John Sommerville

The Problem of Evil

Keller’s theodicy matches mine: God allows temporary suffering for purposes we don’t always know. He allowed his son to suffer extreme physical and spiritual pain on the cross; we can safely assume even suffering works as part of his plan for us.

Though, this is an unsatisfying answer for many, including myself. Why didn’t God just create a world where no suffering was necessary? Like, heaven from the get-go? I mean, you could argue that’s exactly what he tried in the Garden of Eden, and Adam/Eve messed it up. Though, you could also argue God could have restricted their free will, or otherwise created them differently, so that no sin ever occurred.

Regarding Hell, Keller makes an interesting point: the offensiveness of Hell is somewhat unique to the American culture, which emphasizes moral relativism and self-actualization above almost anything else. Judgement is distasteful in America, but a cultural norm in other parts of the world, where they have more issues with the forgiving nature of God!

Why, I concluded, should Western cultural sensitivities be the final court in which to judge whether Christianity is valid?

— Timothy Keller

Is Christianity Growing?

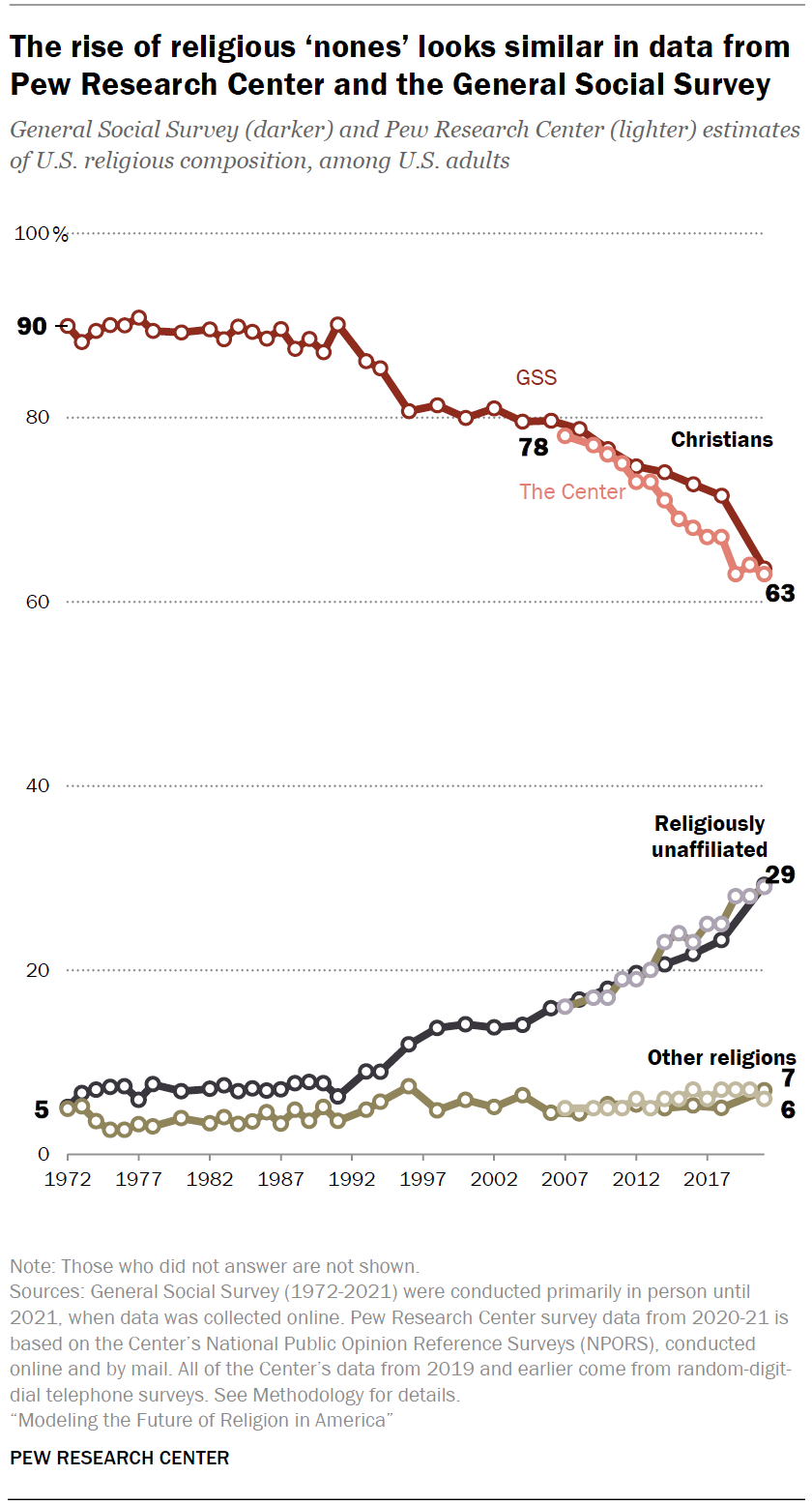

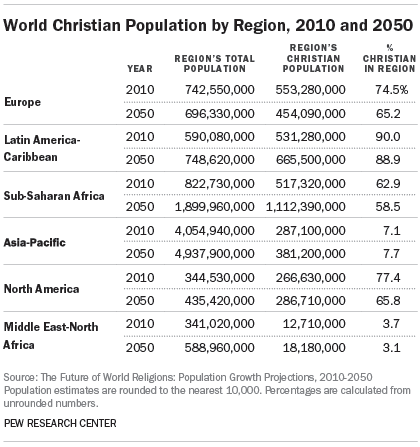

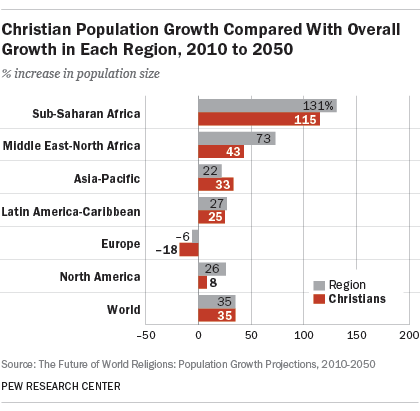

A lot of Christians make claims about whether Christianity is increasing or decreasing. Keller claims the world is “getting both more religious and less religious at the same time,” quoting a poll that shows a “skyrocketed” increase in “no religious preference” answers, and also quoting a (less convincing) poll that Christianity has increased from 1% to “10 to 25 percent” of philosophy teachers and professors. He claims that Christianity is growing in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, and slightly in Europe. Though it definitely appears to me that Christianity is declining in the USA, I wanted to look at some hard data.

Looking at Pew Research Center data seems to roughly confirm what Keller claims.

Click to expand survey and data details...

First, Christianity, and religion in general, is declining in America:

Also as Keller claims, Christianity is becoming more globally diverse:

As noted in a 2011 Pew Research Center report on global Christianity, it has become a more geographically diverse religion since 1910, becoming less concentrated in Europe and more evenly distributed throughout the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa and the Asia-Pacific region.

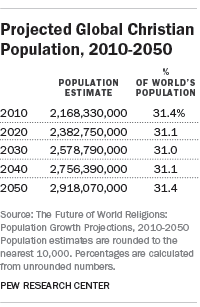

In 2015, Pew Research Center published a lengthy report titled The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050. I strongly recommend you read the report yourself to draw the most accurate conclusions, but I’ve put some discussion below.

Between 2010 and 2050, Christianity’s proportion among the world is expected to remain at about 31.4%, despite some changes to its distribution across the world. Almost every global region will experience a small decline (up to 10%) of Christianity proportional to its population (with the exception of Asia-Pacific). Despite these widespread regional declines, Christianity will remain at 31.4% seemingly because of a massive expected population boom in Sub-Saharan Africa (over 1 billion), which boasts an almost 60% Christian population even in 2050.

Of course, Pew Research Center isn’t the be-all-end-all on religious predictions, but it was good to see some data back up Keller’s claims.

Conclusion

I’ve highlighted some interesting sections above, but of course there were more. Some just weren’t as interesting to me. Some sections were weaker, like his discussion of the physical evidence for the resurrection, and why Christianity must be true since Jesus’s disciples died for the cause. For example, he states “…it is hard to believe that this kind of powerful self-sacrifice would be done to support a hoax,” but what about the martyrs of other religions? But these topics are difficult to condense into a 15 page chapter; for an introduction to these topics, The Reason for God does just fine.

If you’re skeptical of Christianity, or inside Christianity and having doubts, I think this book does a pretty good job of addressing some of those most common issues you’re probably facing. It’s certainly no cure-all for atheism— even Keller himself admits so. But if you go into this book with an open mind, I hope you come out taking Christianity a little more seriously.