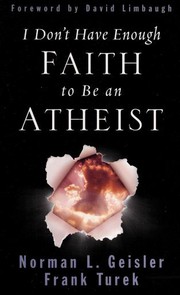

When I opened I Don’t Have Enough Faith to Be an Atheist, I’ll admit that I was expecting to point and laugh. I’m not exactly a huge fan of Norman Geisler and his history of expunging progressive Christians who don’t agree to his fundamentalist views. But by the time I finished the book, I ended with marginally more respect for the authors. Remember, I said marginally.

The basic premise of the book is in the title, but here it is again, spelled out a little more:

Faith covers a gap in knowledge. And it turns out that atheists have bigger gaps in knowledge because they have far less evidence for their beliefs than Christians have for theirs. In other words, the empirical, forensic, and philosophical evidence strongly supports conclusions consistent with Christianity and inconsistent with atheism.

…it is possible that our conclusions in this book are wrong. We don’t think they are because we have good evidence to support them. Indeed, we think our conclusions are true beyond a reasonable doubt… Nevertheless, some faith is required to overcome the possibility that we are wrong.

The book is essentially a really long argument, going point-by-point prove the truth of Christianity from “objective” evidence, concluding that atheism requires more blind faith than Christianity.

Given my low expectations of the book, I was surprised when I started reading the authors’ defense of theism, and actually learned a few things! While I didn’t fact-check everything in this book, some cursory research roughly confirms their arguments about the beginning of the universe, among other things. Unfortunately, as the book continued, the strength of their arguments waned. Truthfully, this is not an academic book, and it was never meant to; the book is full of logical fallacies, cringy “checkmate, atheists” stories, and many arguments were just not compelling in the slightest.

I found myself cringing multiple times at the authors’ accounts of debates, or classroom discussions. Almost every story has a “and then, everyone clapped,” feel to it that just screams exaggeration. For example:

After presenting this information at Harvard University, I received no questions or challenges to my critique of Hume, just stunned silence.

I said, “What power did the New Testament writers gain by asserting that Jesus rose from the dead? The answer is ‘none.’ In fact, instead of gaining power, they got exactly the opposite—submission, servitude, persecution, torture, and death.” They had no answer… I then asked them the question in a different way… Again, they had no response. Why? Because they began to realize that…

When honest skeptics are presented with this question, they typically answer with silence or a stuttering admission that they have no such evidence because none exists.

The book is biased— I mean, even the authors would probably admit to that. While I appreciate their attempts to address counterarguments, the authors have a fairly obvious axe to grind against liberal “tolerance”, evolution, modern education, and atheists in general. The authors’ frequent personal jabs directed at those who disagree just gives the book an unscholarly appearance that doesn’t suggest academic rigor. Good arguments don’t require this low road.

If, as Crossan says, the Resurrection didn’t really occur, then why did Jewish authorities right through the second century continue to insist that the disciples had stolen the body? Crossan has no answer because his theory is false.

Putting aside the book’s serious flaws, it commendably argues a few things: that moral relativism is an indefensible position; that each one of us must reckon with the universe’s inexplicable creation (“why is there something rather than nothing?”); that there is a fair amount of evidence supporting the historical accuracy of the Gospel accounts; and that Christianity is worth considering.

In my opinion, the book is accurate in its assessment that atheism requires a lot of faith in unproven theories— some of which lack even a sniff of evidence (e.g., belief in the spontaneous generation of life, or the mysteries of the Big Bang). As the authors put it, “science is a slave to philosophy.”

But, I’m skeptical that any atheists will read this book and change their mind. As Blaise Pascal, creator of the (in)famous Pascal’s wager, puts it:

People almost invariably arrive at their beliefs not on the basis of proof but on the basis of what they find attractive.

— Blaise Pascal

Weaknesses

The Anthropic Principle

The authors spend a lot of time discussing a related concept called the Anthropic Principle— that all the tiny little mathematical values that have perfectly aligned to give us life on Earth: things like the distance between the Earth and the sun/moon, or the gravitational constant, or the speed of the Earth’s rotation, or it’s axial tilt, etc…

Overall, I didn’t find this argument compelling. The authors also did a poor job responding to their counterarguments. For example, some atheists propose a multiverse theory. Their answer? It’s “an actual impossibility.” I do agree with their conclusion that “the Multiple Universe Theory is simply a desperate attempt to avoid the implications of design”, but they didn’t effectively disprove it:

Second, as we discussed in the last chapter, an infinite number of finite things—whether we’re talking about days, books, bangs, or universes—is an actual impossibility. There can’t be an unlimited number of limited universes.

Materialism

…human thoughts and theories are not comprised only of materials. Chemicals are certainly involved in the human thought process, but they cannot explain all human thoughts. The theory of materialism isn’t made of molecules. Likewise, someone’s thoughts, whether they be of love or hate, are not chemicals. How much does love weigh? What’s the chemical composition of hate? These are absurd questions because thoughts, convictions, and emotions are not completely materially based. Since they are not completely materially based, materialism is false.

An assumption is made that materials “cannot explain all human thoughts” without any evidence. This is circular reasoning. There seems to be an a priori assumption that materialism is false.

Fourth, if materialism is true, then everyone in all of human history who has ever had any kind of spiritual experience has been completely mistaken. While this is possible, given the vast number of spiritual experiences, it does not seem likely. It is difficult to believe that every great spiritual leader and thinker in the history of humanity—including some of the most rational, scientific, and critical minds ever—have all been completely wrong about their spiritual experience.

This reads like a desperate “surely not everyone has been wrong about their spiritual experiences, right???” Formally, this is called an “argument ad nauseum”— a logical fallacy. No evidence is provided. Also, if Christianity is true, then the authors would concede that the vast majority of all spiritual experiences are false (because they occur outside Christianity). Why is it such a stretch to argue that they’re all false?

Darwinists

The authors suggest that the only reason Darwinists don’t just give up is because they fear they’ll lose control, authority, money, or admiration, and they don’t want to follow a religious morality.

Sometimes people refuse to accept what they know to be true because of the impact it will have on their personal lives.

Darwinists would rather suppress the evidence than allow it to be presented fairly. Why? Because this is the one area where Darwinists lack faith—they lack the faith to believe that their theory will still be believed after our children see all the evidence.

That just seems like a bad faith argument (pun intended). But seriously, I highly doubt most Darwinists would agree with that.

Moral Relativism (“Moral Law”)

This chapter is about how people have morality built-in, and it comes from God. Their logic is as follows:

- Every law has a law giver.

- There is a Moral Law.

- Therefore, there is a Moral Law Giver.

I’ve heard this one a thousand times, but to me, it’s just not compelling. I don’t think premise #1 is necessarily true. Their evidence of this line is literally just the following sentence: “Of course, every law has a law giver.” The rest of the chapter is about premise #2.

We can’t not know, for example, that it is wrong to kill innocent human beings for no reason. Some people may deny it and commit murder anyway, but deep in their hearts they know murder is wrong.

Unproven assumption— can the authors read minds? I think some people murder and deep down feel nothing.

In short, to believe in moral relativism is to argue that there are no real moral differences between Mother Teresa and Hitler, freedom and slavery, equality and racism, care and abuse, love and hate, or life and murder… We all know that such conclusions are absurd. So moral relativism must be false. If moral relativism is false, then an objective Moral Law exists.

OK, the authors just defined Moral Relativism, used an appeal to emotion to make it sound absurd, then use the bandwagon fallacy (“we all know such conclusions are absurd”) to prove their point.

The authors make a weak argument that a moral law can’t come from evolution, because if it did, why do people sometimes die for noble causes, or do drugs (isn’t the end goal of evolution to survive?). I don’t find this argument compelling; it’s entirely possible that in the course of human history, tribes that contained members with sacrificial tendencies ended up “winning” the evolutionary battle and passing on their genes. Addictive are a recent invention, and evolution hasn’t had enough time to deal with it.

Overall, the authors don’t prove that a universal “moral law” definitely exists. In real life, people disagree about almost everything. Even “universally” accepted morals like “killing babies is wrong” are not really universal; there are people on Earth that don’t agree. Also, “universal” morals change over time with society.

Polytheism

Among the major world religions, the authors only consider the 3 Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, Islam) to be “theistic” because their definition of the term excludes polytheism.

why does the existence of a theistic God disprove polytheism? …because God is infinite, and there cannot be more than one infinite Being. To distinguish one being from another, they must differ in some way. If they differ in some way, then one lacks something that the other one has. If one being lacks something that the other one has, then the lacking being is not infinite because an infinite being, by definition, lacks nothing. So there can be only one infinite Being.

In my opinion, this is a weak argument; even Christianity can be called polytheistic by this definition, because we recognize three co-equal, co-eternal, infinite beings. While the trinity may share one essence of being “God”, they are distinct. (I’m not necessarily saying here that I believe Christianity is polytheistic, merely that it could be called polytheistic by some definitions, including the one the authors provide.)

Of course, if polytheistic religions weren’t ruled out at this point in the book, the authors would rule them out later when they state that any religion that denies the Bible is false.

Perfect Being Fallacy

I found several examples of the authors using the Perfect Being fallacy, which attempts to assign characteristics to God based on a subjective definition of “perfect”. In other words, it’s assuming God would act a specific way because we think that’s what a Perfect Being would do.

it could be that none of these world religions is completely true. Maybe they have theism right but little else. That’s possible. However, since we know beyond a reasonable doubt that God exists and that he has the characteristics we’ve listed above—characteristics that include design, purpose, justice, and love—then we should expect him to reveal more of himself and his purpose for our lives. This would require that he communicate with us.

God is not likely to do miracles for mere entertainment purposes.

Contradictory Gospels

In light of the numerous divergent details in the New Testament, it’s clear that the New Testament writers didn’t get together to smooth out their testimonies… if they were making up the New Testament story, they would have gotten together to make sure they were consistent in every detail. Such harmonization clearly didn’t happen, and this confirms the genuine eyewitness nature of the New Testament and the independence of each writer.

This argument has been repeated since John Chrysostom in the 300s AD, but I just don’t find it compelling. If the Bible truly is divinely inspired, why would the Gospels contain discordant or contradictory historical statements? How does that confirm its truthfulness? These authors supposedly had the power of the Holy Spirit assisting them in their testimonies.

I concede that these differences “confirm the genuine eyewitness nature of the New Testament and the independence of each writer”, but they don’t suggest divinity.

Ironically, it’s not the New Testament that is contradictory, it’s the critics. On one hand, the critics claim that the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) are too uniform to be independent sources. On the other hand, they claim that they are too divergent to be telling the truth. So which are they? Are they too uniform or too divergent?

Here, the authors refuse to discuss what is the predominant theory among scholars regarding Gospel authorship: that Mark was written first, then Matthew or Luke, then the other, then John; each later Gospel uses the earlier Gospels as source documents, along with unknown other sources, and makes changes as they see fit1. It’s exactly like the critics suggest— the Gospels are too uniform (Gospels frequently include word-for-word copies of entire paragraphs from earlier Gospels) to be composed completely independently, but too divergent to be telling a single historical story. In my opinion, this is another case of a bad faith argument that doesn’t really attempt to refute the critics’ argument.

even if one could find some minor details between the Gospels that are flatly contradictory, that wouldn’t prove the Resurrection is fiction. It may present a problem for the doctrine that the Bible is without any minor error, but it wouldn’t mean the major event didn’t happen.

I’m glad the authors acknowledge the possibility of “minor errors” in the Bible, and that it wouldn’t necessarily falsify the resurrection. I do believe the Bible contains at least minor historical errors, but it’s not a problem for my faith or doctrine, because I don’t believe in strict literalistic inerrancy— in other words, I don’t read the Bible like a history textbook.

Biblical Inerrancy

First, let’s spell out logically why the Bible can’t have errors:

- God cannot err.

- The Bible is the word of God.

- Therefore, the Bible cannot err.

I take issue with premise #2: the Bible is more than just the word of God; it’s distinguishable from God opening the heavens and directly speaking to us. There is something human about the Bible, and I concede that this is hard to understand, but to merely state that the Bible is “the word of God” is reductionist. (Just go read Jesus, Contradicted.)

First, because Jesus’ authority is well established by the evidence, we reasonably give the benefit of the doubt to the Bible when we come across a difficulty or question in the text. In other words, when we run across something inexplicable, we assume that we, not the infinite God, are making an error… However, that doesn’t mean we believe there’s absolutely no possibility for Bible errors… But to this day, after nearly 2,000 years of looking, no one has found such an irreconcilable problem.

Whether or not the Bible contains “irreconcilable problems” is up for debate. I concede that most Bible “difficulties” are easily solvable using the authors’ techniques (e.g., the varying amounts of angels at the tomb), but many are not. Some of the most troublesome “problems” include: Jesus’ varying genealogies in Matthew and Luke, or that 1 Samuel 21 calls the high priest of the time Ahimelech while Jesus in Mark 2 says his name was Abiathar. I’m not going into the details here, but the evidence for irreconcilable problems in the Bible is significant. Unfortunately, the authors admit they ignore this evidence, and just assume the Bible is inerrant.

because Jesus’ authority is well established by the evidence, we reasonably give the benefit of the doubt to the Bible when we come across a difficulty or question in the text. In other words, when we run across something inexplicable, we assume that we, not the infinite God, are making an error.

Critics may also charge, “But your position on inerrancy is not falsifiable. You will not accept an error in the Bible because you’ve decided in advance that there can’t be any!”

In fact, our conclusion on inerrancy would be falsified if someone could trace a real error back to an original scroll.

That is an extremely high bar— we don’t have any original scrolls of any books of the Bible, Old or New Testament. At this point, it’s likely we will never find them. The authors claim they’re open-minded to being wrong, but they already admitted they presuppose inerrancy. Based on the absurd conditions they’re requiring to be wrong, I don’t believe the authors are really open-minded.

Even if the Scriptures are found to contain a false detail or two, the historical truth of Christianity will not be diminished. We hasten to add, we don’t think inerrancy will ever be falsified, but if it is, Christianity will still be true beyond a reasonable doubt.

I appreciate their humility in accepting that the Bible could be inerrant without invalidating the resurrection.

Unlike most other religious worldviews, Christianity is built on historical events and can therefore be either proven or falsified by historical investigation.

While it’s true that Christianity makes historical claims, these claims are barely provable— the Bible discusses events that happened so long ago, I don’t think we can ever indisputably “prove” whether it’s inerrant or not. Christianity also makes plenty of unprovable religious claims like that Jesus rose from the dead.

If, after 2,000 years of looking, no one can find the remains of Jesus or real errors in the Bible, isn’t it quite possible that neither exist?

Again, plenty of biblical contradictions have been noticed and cataloged… but if you presuppose the Bible can’t contain errors, then ta-da! those “errors” disappear!

Development of Biblical Canon

First, we need to clear up a common misunderstanding about what we call “the canon.” It is this: It’s wrong to say that “the church” or the early church fathers determined what would be in the New Testament. They didn’t determine what would be in the New Testament—they discovered what God intended to be in the New Testament.

Yes, the early church fathers did determine which books were canon, and the church fathers had different opinions about which books were really canon. Whether each book they chose is actually inspired, is still up for debate to this day— just ask Martin Luther, who thought in the 1500s that Hebrew, James, Jude, and Revelation weren’t as legitimate as the rest of the New Testament— going so far as to put them at the end of his Bible translation, in a different section.

It wasn’t until the 1500s with the Reformation and the Catholic’s Council of Trent that the official boundary lines of biblical canon were finally drawn. The early church fathers didn’t even have a concept of “canon”; they didn’t see the New Testament books as either “fully inspired and authoritative” or “complete human nonsense”— in their time, there was nuance, and certain books were considered somewhat authoritative and taught from without being fully “Scripture” (e.g. the deuterocanonical books).

While the major works of the New Testament were immediately seen as authentic by these early church fathers, most of the New Testament was accepted before A.D. 200, and all of it was officially and finally recognized as authentic by the Council of Hippo in 393.

What the authors don’t mention is that the Council of Hippo also declared the deuterocanonical books (“The Apocrypha)” as canonical. For Protestants, that’s a problem, and should cast a shadow on their judgement. But, it is true that this council’s NT canon matches what we have in our Bibles today.

Speculation on God’s Decisionmaking

Among other things, God is omniscient and omnipotent. He had the power to create any universe he wanted— including one where all humans live alongside God, and lack the “free will” or ability to do any evil. God could even create humans such that we would never want to do evil, and we wouldn’t even know our free will was being suppressed. There would never be any sorrow, sadness, death, or crime. Sounds like paradise.

For some reason, this is not the universe God created. For some reason, God created angels and demons (including Satan), and human beings with free will and the ability to perform great (and small) evil. In this universe, he sends his son Jesus to die on the cross for our sins, and gives us the choice to admit our sin and accept Jesus, or live in ignorance of what God did for us. For those who don’t choose Christ, the Bible tells us they are destined to an unfortunate eternal future apart from God. Even more still, Paul writes that God predestined us before we were born; Christians have spent centuries deciphering how that works with free will, but I digress.

The point is, God had a choice, and he chose our universe. Unless God releases more Scripture, we’ll never know why. We can attempt to reason why God makes his decisions, but it’s an exercise in futility.

For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts.

— Isaiah 55:9

The Bible makes this clear— we have an entire book, Job, about a blameless man who is tortured for inexplicable reasons. When he finally breaks down in front of God, here’s what God says in response:

Dress for action like a man; I will question you, and you make it known to me. Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding. Who determined its measurements—surely you know!

— Job 38:3-4

Once God finishes questioning Job, Job responds:

Then Job answered the LORD and said: “I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted. ‘Who is this that hides counsel without knowledge?’ Therefore I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know… therefore I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes.”

— Job 42:1-6 (shortened for clarity)

The story’s ending? Job receives an unexplained blessing.

And the LORD restored the fortunes of Job, when he had prayed for his friends. And the LORD gave Job twice as much as he had before.

— Job 42:10

We are not meant to understand God. His ways and thoughts are above ours, and though we are sometimes given an explanation for God’s actions, to attempt to understand his reasoning is futile. This is why I feel such disdain for some of the authors’ ideas, like that God, in his infinite wisdom, refuses to give us more obvious testimony, because then picking him would be too easy. To put it simply, it’s ridiculous to even attempt to explain God’s actions. You don’t have to take my word for it— even Paul called God’s judgements “unsearchable”:

Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!

— Romans 11:33

I’ll never understand why God made (and continues to make) the choices He does, but that’s part of being Christian— you have to have faith that He is God, He knows more, and He is good. The thing is, having that faith is hard. So in multiple places throughout the book, the authors tried to assign rationality to God’s “unsearchable” judgements (examples below). The thing is, these explanations are complete speculation, and it falsely teaches Christians and atheists alike that “if you think about it hard enough, you can understand God’s reasoning!”

taking the form of a human servant was the only way he could offer us that salvation without negating our ability to accept it.

In order to respect your free choice, God has made the evidence for Christianity convincing but not compelling.

You say, “God doesn’t send anyone to hell!” You’re right. If you reject Christ, you’ll send yourself there.

God is too loving to destroy those who don’t want to be in his presence.

Skeptics may ask, “Well, if the New Testament really is the Word of God, then why didn’t God preserve the original?” We can only speculate here, but one possibility is because his Word might be better protected through copies than through original documents. How so? Because if the original were in someone’s possession, that person could change it. But if there are copies spread all over the ancient world, there’s no way one scribe or priest could alter the Word of God.

Strengths

The Big Bang

The authors use the Second Law of Thermodynamics, redshift, radiation, and a few other arguments in support of the Big Bang theory. My preliminary research shows that indeed, the Big Bang is currently the consensus explanation for the beginning of the universe, and their evidence is solid. Though, the authors point out that the Big Bang theory doesn’t have to be true for Christianity to be true. If you admit that something “caused” the Big Bang, then what exactly was it?

The Second Law of Thermodynamics… states, among other things, that the universe is running out of usable energy… in other words, the universe has only a finite amount of energy (much as your car has only a finite amount of gas)… in the same way, the universe would be out of energy by now if it had been running from all eternity.

Not the best analogy— when I read “the universe has only a finite amount of energy” I immediately winced at the contradiction with the law of conservation of energy— but to say that “usable energy” is dwindling is correct.

When you get right down to it, there are only two possibilities for anything that exists: either 1) it has always existed and is therefore uncaused, or 2) it had a beginning and was caused by something else… According to the overwhelming evidence, the universe had a beginning, so it must be caused by something else—by something outside itself… So what is this First Cause like? …self-existent, timeless, nonspatial, and immaterial…

Universalism

In fact, world religions have more contradictory beliefs than complementary ones. The notion that all religions teach basically the same thing—that we ought to love one another—demonstrates a serious misunderstanding of world religions… they disagree on virtually every major issue, including the nature of God, the nature of man, sin, salvation, heaven, hell, and creation!

The Gospels are Not Ideal

In chapter 11, the authors make a strong case that if the gospel authors were completely fabricating their gospels, it’s unlikely they would have included all the “embarrassing” or “demeaning” or “difficult” details that they did. They provide many examples of this, like:

- Jesus is not believed by his own brothers

- Jesus is deserted by many followers

- Jesus says “The Father is greater than I”

- Jesus gives extremely difficult commandments like “be perfect” and “If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also” and “love your enemies”

- Women were the first witnesses of the empty tomb, including Mary Magdalene (who was previously demon-possessed)

Alternative Resurrection Explanations

In one chapter, the authors discuss the potential explanations for Jesus’ apparent resurrection. They begin by stating that “No one from the ancient world—not even the enemies of Christianity—has offered a plausible alternative explanation for the Resurrection”, but in my opinion, several of the explanations they argue against are plausible. Regardless, the authors put forward some strong arguments against many of the theories.

Hallucination

hallucinations are not experienced by groups but only by individuals.

There is evidence that refutes this argument. Mass hysteria is a real thing. For example, Catholics regularly see Mary in groups, which I assume Protestants would call a “hallucination” given their low view of Mary (relative to Catholicism).

The existence of the empty tomb is the second fatal flaw with the hallucination theory. If the 500-plus eyewitnesses did have the unprecedented experience of seeing the same hallucination at twelve different times, then why didn’t the Jewish or Roman authorities simply parade Jesus’ body around the city? That would have ended Christianity once and forever.

Fair point— the hallucination theory also requires a lone wolf to rob the tomb, allowing the remaining unknowing disciples to experience the hallucination.

Wrong Tomb

if the disciples had gone to the wrong tomb, the Jewish or Roman authorities would have gone to the right one and paraded Jesus’ body around the city. The tomb was known by the Jews because it was their tomb (it belonged to Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Jewish Sanhedrin). And the tomb was known by the Romans because they placed guards there. As William Lane Craig notes, the wrong tomb theory assumes that the all of the Jews (and the Romans) had a permanent kind of “collective amnesia” about what they had done with the body of Jesus.

Apparent Death

First, enemies and friends alike believed Jesus was dead. The Romans, who were professional executioners, whipped and beat Jesus brutally to the point of his collapse. They then drove heavy, wrought-iron nails through his wrists and feet, and plunged a spear into his side… Moreover, Pilate checked to make sure Jesus was dead, and Jesus’ death was the reason the disciples had lost all hope.

Jesus was embalmed in seventy-five pounds of bandages and spices. It is highly unlikely that Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus (John 19:40) would have mistakenly embalmed a living Jesus.

even if everyone was wrong about Jesus being dead when he went into the tomb, how would a badly injured and bleeding man still be alive thirty-six hours later? He would have bled to death in that cold, damp, dark tomb.

even if he did survive the cold, damp, dark tomb, how could he unwrap himself, move the two-ton rock up and away from the inside of the tomb, get by the elite Roman guards (who would be killed for allowing the breach of security), and then convince the scared, scattered, skeptical cowards that he had triumphed over death?

Disciples Stole the Body

Why would the disciples embark on such a self-defeating conspiracy? And why did every one of them continue to say that Jesus had risen from the dead when they could have saved themselves by recanting that testimony?

how did the disciples get past the elite Roman guards who were trained to guard the tomb with their lives?

A Substitute on the Cross

The authors effectively dispel this theory. It has no evidence, and as the authors write, “How could so many people be wrong about a simple identification?” It also requires the believers to rob the tomb of the dead substitute. Even the Jewish Talmud asserts that Jesus died on the eve of the Passover.

Disciples’ Faith Led Their Belief in the Resurrection

The authors don’t provide much to refute this one. Apparently William Lane Craig argued once in a debate that “The faith of the disciples did not lead to the [resurrection] appearances, but it was the appearances which led to their faith; they then searched the scriptures.” This sounds like circular reasoning. But, the authors argue that “the scared, scattered, skeptical disciples were not of the mind to invent a resurrection story and then go out and die for it”, and this theory doesn’t account for Jesus appearing to the 500 in the Gospels.

Footnotes

-

Read Jesus, Contradicted by Michael Licona if you want to learn more. ↩