Within Protestantism, there are three major interpretations of the doctrine of Hell:

- Eternal Conscious Torment (ECT) : unbelievers will be tortured for eternity outside of God’s presence, while believers will spend eternity in heaven with God

- Annihilationism/Terminal Punishment: unbelievers will be tortured in hell for a period of time, then permanently “annihilated” (i.e. removed from existence)

- (Christian) Universalism: unbelievers will be tortured in hell for a period of time, then re-joined with God and spend eternity in heaven

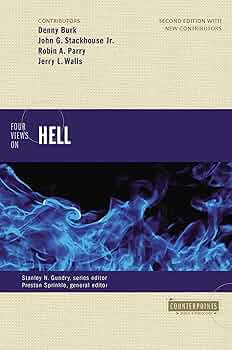

I was unable to find a survey online of Protestants and exactly how popular each view is, but I feel confident asserting that the first view, ECT, is by far the majority interpretation within Protestantism. Four Views on Hell gives space for authors to argue for each of these viewpoints, as well as a 4th perspective on Purgatory, which did not seem relevant to this discussion. As several of the book’s authors suggest, the minority views (Annihilationism and Universalism) are gaining popularity in younger generations. This should not be surprising; ECT has never been an attractive position (regardless of its truthfulness).

Most readers will already have a view firmly fixed in their mind. I would encourage you, the reader, to hold onto this view loosely as you consider the arguments in this book. If you hold onto your view too tightly, unwilling to reexamine it in light of Scripture, then you are placing your traditions and presuppositions on a higher pedestal than Scripture itself. If the view you have always believed is indeed Scriptural, then there’s nothing to fear by considering and wrestling with other views. If Scripture is clear, then such clarity will be manifest. But there’s a chance that the view you currently hold to is not a biblical one. And we all, therefore, need to be open to having our preconceived views corrected by Scripture.

— Preston Sprinkle

As the book’s editor (Sprinkle) suggests, this book is unlikely to change anyone’s mind— in my experience, few Protestants truly have an open mind about traditional dogmas. I found the book’s discussion to be somewhat enlightening, but I largely walked away unsatisfied. I don’t necessarily blame the authors, though; systematizing the Bible into any consistent framework is an inherently difficult task.

I noticed a pattern in several arguments across multiple authors. Before I explain what it is, here are some examples:

- From Denny Burk in his pro-ECT essay: “since God is infinitely holy/good, any sin against him (which we commit daily) deserves infinite punishment” (my own paraphrasing).

- From John Stackhouse, in a pro-Purgatory response: “This Protestant hope of more-or-less instant sanctification [after death/at Jesus’s return], however, poses two questions: (1) If sanctification can be given in an instant at the end of life, then why does God not give it to us now? (2) If sanctification is only gradual and difficult in this life, why do we expect that it will be different in the life to come?”

- Jerry Walls: “Finite creatures, after all, can only do a finite amount of evil and cause a limited amount of harm in the space of their short lives, so infinite punishment seems way out of proportion to the crime.”

I find these “logical” deductions quite absurd, and even funny. I often read people using these tactics to draw nonsensical conclusions about God, the world, and various doctrines. Several mainstream Christian doctrines are explicitly illogical (e.g. the Trinity, or Jesus’s “100% God, 100% human” dual nature), which should discourage this kind of behavior; it’s plausible that we should consider a doctrine’s illogicality as a strength! In any case, it’s practically impossible to prevent speculation of this nature; as post-Enlightenment readers, we just can’t help but feebly attempt to systematize and unify Christian doctrine from the dozens of biblical authors, who probably wouldn’t even agree on the doctrines in question anyways! I, myself, am plenty guilty of this: take a prooftext here, a prooftext there, sprinkle in some dubious logic, and you’ve got yourself a fine doctrine. It might genuinely be a necessary part of the systematization process.

Regardless, I did learn things from this book— namely, the common arguments Christians make for different doctrines of hell (shocker). Every author had insightful contributions, from the most conservative to the most liberal. Though, it’s quite depressing to spend so much time thinking about hell. If Burk/the ECT camp is correct, most of humanity is destined for eternal conscious torture. As Stackhouse aptly states, “It is literally too horrible to consider.” I can’t imagine being a scholar who specializes in this area.

Denny Burk: Eternal Conscious Torment (ECT)

Presenting the traditional, majority view, Denny Burk spent most of his essay using 10 biblical passages to defend ECT— and he did so strongly. While it’s true that Burk skips over some passages that undermine his view, his chosen passages practically make the argument for him; little interpretation is necessary. There is no shortage of verses that support that idea of eternal/everlasting punishment for unbelievers.

But, ECT is not without heavy criticism. Most non-Christians find the ECT view of hell to be anything but “love”— which God, they’re told, embodies. The premise of ECT is a significant part of the Problem of Evil, a long-debated issue that pushes people away from the faith to this day. If there was stronger biblical evidence against ECT, I think it would be quickly rejected. Unfortunately, that does not seem to be the case. Here’s to hoping that Parry’s view of Christian Universalism turns out to be accurate.

Burk’s view of God’s agenda entails a monstrously egotistical God who deals loftily with his hapless creatures as mere instruments of his self-aggrandizement.

— John Stackhouse

God’s Failure?

One large criticism of ECT, and Hell more broadly, is that its existence means failure of both God’s wishes, and Jesus’s death on the cross. Parry hits this point hard in the book. Consider 1 Timothy 2:3-4: “God our Savior… wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth.” Or 1 John 2:2, “[Christ] is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for ours but also for the sins of the whole world.” Surely, if God wants something, and Jesus is even said to die for it, it will be accomplished? As Parry argues strongly in his pro-Universalism essay: “…it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the biblical story told in a non-universalist way ends in a tragic partial failure for God.”

If I were to offer a pro-ECT defense against this argument, it would be that there is a biblical standard for God failing to achieve what he wants— God wants an obedient Israel, an obedient Adam and Eve, the eternal life of all… and yet, these goals are frequently thwarted. If God is all powerful, but fails to achieve what he explicitly “wants”, then perhaps the word “want” is insufficient to communicate God’s ultimate goals. In a similar way, if I complain on the way to the grocery that “ugh, I really don’t want to go to the grocery,” then why am I in the car, on the way to the grocery? I always had a choice to go; I am in the car strictly because I do want to go to the grocery (probably because I want food). We humans often do things we “don’t want” in this way. Perhaps, in a similar way, God speaks (or, biblical authors write) of his “wants” in a superficial way; he is said to “want” or “not want” something, but this is only a surface-level description of God’s true goals. I’m not sure how else to resolve this issue, besides suggesting that God cannot achieve his goals, which is assuredly unbiblical.

NOTE: After writing this, I’ve stumbled across the terms antecedent will and consequent will, which Thomas Aquinas writes about in Summa Theologiae, Chapter 19. One useful definition says that antecedent will is what God wills before taking into mankind into account, and consequent will is afterwards. Aquinas gives a much better analogy than I did: he likens God to a “just judge, that antecedently he wills all men to live; but consequently wills the murderer to be hanged.” Though, I would argue that if a just judge wants to hang murderers, and even knows he wants to hang murderers (and that murderers exist), can he really say he “wills all men to live”?

Another possible defense, from Burk himself, is that God’s goal is merely for all to be right within the universe. This doesn’t require Universalism and rescue of hell-bound souls; it only requires atonement for sins, which is exactly what Hell accomplishes. In my view, this defense is weak, especially, when taking passages like 1 Timothy 2:3-4 into account; there is a biblical basis for believing that God truly “wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth”, not merely for things to be right with the world.

Violated Fairness?

One of the biggest criticisms of ECT, and God’s judgement in general, is that it violates our sense of fairness. Especially for those Calvinists who believe in predestination/determinism (a view I find largely biblical and biologically evident), why would God create people knowing they are destined specifically for eternal, conscious torture? Romans 9 directly addresses this issue, so I think it’s worth mentioning.

…when Rebekah had conceived children by one man, our ancestor Isaac – even before they were born or had done anything good or bad (so that God’s purpose in election would stand, not by works but by his calling) – it was said to her, “The older will serve the younger,” just as it is written: “Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated.”

What shall we say then? Is there injustice with God? Absolutely not! For he says to Moses: “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.” So then, it does not depend on human desire or exertion, but on God who shows mercy. For the scripture says to Pharaoh: “For this very purpose I have raised you up, that I may demonstrate my power in you, and that my name may be proclaimed in all the earth.” So then, God has mercy on whom he chooses to have mercy, and he hardens whom he chooses to harden.

You will say to me then, “Why does he still find fault? For who has ever resisted his will?” But who indeed are you – a mere human being – to talk back to God? Does what is molded say to the molder, “Why have you made me like this?” Has the potter no right to make from the same lump of clay one vessel for special use and another for ordinary use? But what if God, willing to demonstrate his wrath and to make known his power, has endured with much patience the objects of wrath prepared for destruction?

— Romans 9:10-22

In a way similar to how God responds to Job, Paul says God is God, so he can do whatever he wants. Or, as I’ve often heard, you can argue that believers should be thankful for their undeserved opportunity to experience heaven (regardless of how few of them there are). Neither solution is satisfying.

Annihilationism

Annihilationism, or “conditional immortality”, teaches that unbelievers, having rejected Jesus’s atoning work on the cross, must atone for their own sins after bodily death by suffering in Hell. Afterwards, unbelievers will undergo a permanent “second death” or cease to exist. John Stackhouse argues that we should re-interpret passages of hell and pay attention to the words “eternal”, “destroy”, and “death”. For example:

- Is God’s “unquenchable fire” a literal description of hell, or just a symbolic statement of God’s propensity to destroy evil?

- When the Bible uses the Greek word typically translated “eternal”, should we assume it really means eternal, or should we doubt since we have other biblical instances of supposedly “eternal” things ending (e.g. priesthood of Exodus 29, Solomon’s eternal temple, the “eternal” sin of Mark 3)?

- When the Bible says Jesus will destroy the devil (Hebrews 2:14), does that mean Jesus literally destroys the devil, or is it just symbolic victory language?

- When Revelation speaks of “the second death” in the lake of fire, does it mean a permanent death, or is it symbolic of the suffering and separation inside?

- When Romans 3:23 says “The wages of sin is death”, is Paul referring to annihilationism, or just symbolic/spiritual death?

God’s cosmos cannot remain entirely and forever good if remnants of Satan or Death or wicked humans persist.

— John Stackhouse

Stackhouse is convinced that God cannot “win” if sin and death remain in the universe: they must be annihilated to finish the job. Burk, on the other hand, is convinced that God only needs to judge the sinful in order to make things right— eternal torture is not a problem. Both sides seem to be speculating.

Christian Universalism

Christian universalism is the view that in the end God will reconcile all people to himself through Christ.

— Robin Parry

Though it’s an oft-criticized minority position within Protestantism, Christian Universalism does have the support of many historical Christians— even some big names, like Origen, Clement of Alexandria, and possibly others like Athanasius or Basil of Caesaria. In terms of a scriptural basis, Parry thinks we each read into the Bible what we want to see; there are passages that support every doctrine of hell. But, he argues, when we consider all passages together, a fuller picture of hell and redemption emerges.

As an example, Parry points to the doctrine of divorce: in Mark, Jesus leaves no legitimate reasons for divorce. In Matthew, he gives 1 reason. In 1 Corinthians, Paul adds another. Readers can use Mark to prooftext a total ban on divorce, but they’d be missing the fuller picture from Matthew and 1 Corinthians. Parry argues that anti-Universalists make the same mistake: “The issues for evangelicals is how to affirm all of these texts as sacred Scripture, how to interpret them in relation to each other, and how to hold their teachings together.” A small point of evidence supports Parry’s cause: several passages that translate to “eternal punishment” use a Greek word that could be translated as “in an age to come”, meaning they’re not necessarily statements about the length of heaven/hell, but rather pointing out that the events will happen far into the future.

I agree with Parry that scripture can often be used to prooftext specific positions, but should be taken with more nuance and a “big picture” mindset. If pro-ECT Christians want to prooftext, Parry can play the game too:

- [Christ] is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for ours but also for the sins of the whole world. (1 John 2:2)

- For Christ’s love compels us, because we are convinced that one died for all, and therefore all died. (2 Cor. 5:14)

- This is good, and pleases God our Savior, who wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth. For there is one God and one mediator between God and mankind, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all people… (1 Tim. 2:3–6)

- But we do see Jesus, who… suffered death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone. (Heb. 2:9)

- God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him (John 3:17)

- I, when I am lifted up from the earth [on the cross], will draw all people to myself (John 12:32)

Using these passages, Parry makes a simple and powerful argument:

This teaching emphasizes the mainstream Christian view that God desires to redeem all people (1 Tim. 2:4; 2 Peter 3:9) and has acted in Christ in order to do so. So the provocative questions here are these: Will God’s desire to save all people be satisfied or eternally frustrated? Will the cross save all those for whom Christ died, or will his death have been in vain for some people?

— Robin Parry

I already wrote about this in the ECT section, but the core issue is: does God really wish to save all people, or is this just language for one of God’s “lower goals”— in other words, are there more important goals (e.g. avoiding violating free will) such that God is willing to let some people be unsaved? A strong case can be made that yes, there are such higher goals, or “divine goods” as Christian philosopher Michael Rea argues. But, the biblical language is plain: God “wants” and “wishes” to save all. Parry writes that “…it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the biblical story told in a non-universalist way ends in a tragic partial failure for God”, and I see where he’s coming from. Regardless, Parry suffers by being in the traditional and scriptural minority, and for those reasons, Christian Universalism (attractive as it is) will likely remain a minority position.

A Quick Aside on Purgatory

Jerry Walls provides the fourth and final essay, in defense of Purgatory. Contrary to my incoming expectations, Walls explains that Purgatory is only for believers bound for heaven (which is standard doctrine); it’s main purpose is to santify (i.e. to make like Christ) believers. The logic goes like this: only perfect people are allowed into heaven, but upon death, we are far from perfect; surely lots of post-death time is required for us to grow into a being that is ready for heaven. That time is spent in Purgatory, which is like a “bridge” to heaven. Purgatory is certainly not hell, but there will probably be pain in Purgatory— not as retributive punishment for our sins (as some historical Christians believed, and some still do), but Walls says “the pain is due essentially to the radical transformation we must undergo in order to become the sort of persons who could truly welcome a God of perfect holiness to take up permanent residence in every part of our lives.” I’m not convinced the pain is necessary or that it logically follows from the doctrine.

Walls is aware that “there is little explicit biblical support for the doctrine [of Purgatory]”— I and the responding authors agree. He likens the doctrine of Purgatory to the doctrine of the Trinity— both require “disciplined speculation”. His main supporting passage is 1 Corinthians 3:11-15. I’m usually willing to give interpreters the benefit of biblical ambiguity, but in this case, I fail to see Walls’s interpretation anywhere in this text. In addition, as Parry points out, 1 Corinthians 15:51-52 and 1 John 3:2 both support instantaneous sanctification upon Jesus’s return— a direct contradiction of Walls’s entire argument.

As a final, unrelated note on Walls’s writing, I found this section particularly egregious:

Indeed, I think we should be wary of pitting tradition against Scripture, as Stackhouse seems to do when he urges that evangelicals should stand “on what one thinks the Bible says, whatever the tradition might be.” Now, some tradition, of course, is extrabiblical, and I would certainly agree with Stackhouse concerning that sort of tradition. However, when a traditional doctrine is one that is rooted in biblical exegesis and enjoys centuries of consensus going back to the earliest Fathers and across all branches of the church, one should give it every benefit of the doubt.

— Jerry Walls

This is a great example of how “tradition” can be manipulated by Protestants to perform any rhetorical goal. Walls’s position that “extrabiblical tradition” should be thrown out in exchange for those “rooted in biblical exegesis” is a defensible position, but the issue is: who gets to decide which is which? Here we have a scenario where Stackhouse argues that Annihilationism is strongly biblical, uses evidence to argue in its favor, and Walls can easily step back and say “woah woah woah, let’s not throw out old traditions!” When tradition works in his favor, he’s going to call on its authority, and when it doesn’t, it can safely be ignored.